Esteban Hotesse

The Only Dominican-Born Member of the Tuskegee Airmen

Esteban Hotesse superimposing a B-25 Mitchell medium bomber assigned to the Tuskegee Airmen.

Esteban Hotesse joined the United States Army Air Corps during World War II. One of the few Latino men to enlist in the U.S. Armed Forces, Esteban was an additional rarity considering he was black. He made history by becoming the first Afro-Latino member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen, the only all-black elite group of military pilots in the U.S. Army Air Corps (the precursor of the U.S. Air Force).

Esteban Hotesse was born in Moca, Dominican Republic, on February 2, 1919. When he was four years old, he immigrated to the U.S. through Ellis Island with his mother, Clara Pacheco, and his two-year-old sister, Irma Hotesse. His mother, who was 25 at the time, settled the family in Manhattan.

In February 1942, when he turned 23, Esteban enlisted and eventually earned the rank of second lieutenant. He was still living in Manhattan with a Puerto Rican wife named Iristella Lind at the time, along with their two daughters. Over a year later, in April 1943, they applied for citizenship. According to his records, Esteban had been a semi-skilled construction worker.

Portrait of Esteban Hotesse. Illustrated by Daniel J. Middleton.

Like his fellow black compatriots, Esteban experienced racism and segregation during his time in the Air Corps. But because civil rights leaders pushed for racial inclusion, a few changes occurred. Esteban’s squadron became part of the 477th Bombardment Group M, which moved to a base in Kentucky—Freeman Army Airfield—less than three miles from Seymour, Indiana, a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan. The airfield became the setting for the so-called Freeman Field mutiny.

It all started in April 1945, when black officers learned that the man in charge of Freeman Army Airfield, Colonel Robert B. Selway, had created two Jim Crow clubs. Club Number One was for black officers, now classified as “trainees,” and Club Number Two was for white officers, deemed “instructors.” Colonel Selway also issued an order that defined the new regulation in detail, which the black officers were to read and agree to by affixing their signatures.

Members of the 477th Bombardment Group.

In all, 101 officers, including Esteban Hotesse, refused to sign. They protested by peacefully entering the whites-only club in turn and demanding service. The officers were all arrested for violating base regulations. They awaited trial at Godman Field. Members of several black organizations, labor unions, and Congress voiced their disapproval of the arrests.

Pressure from the collective voice of protest forced the War Department to yield. On the orders of Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, all 101 officers were released on April 23, though each had an administrative reprimand placed in their file. The brave protest of the officers became a blueprint for effecting change through civil disobedience.

Less than three months after the protest, Esteban died. On July 8, 1945, Esteban and several men engaged in a military exercise over the Ohio River. At one point, they could not regain altitude after the aircraft flew too low and struck the water. According to the War Department’s official report:

“The aircraft crashed into the Ohio River in Indiana killing the pilot, copilot, and Hotesse. It was reported that upon impact the cockpit and tail broke away from the aircraft.”

You may also be interested in:

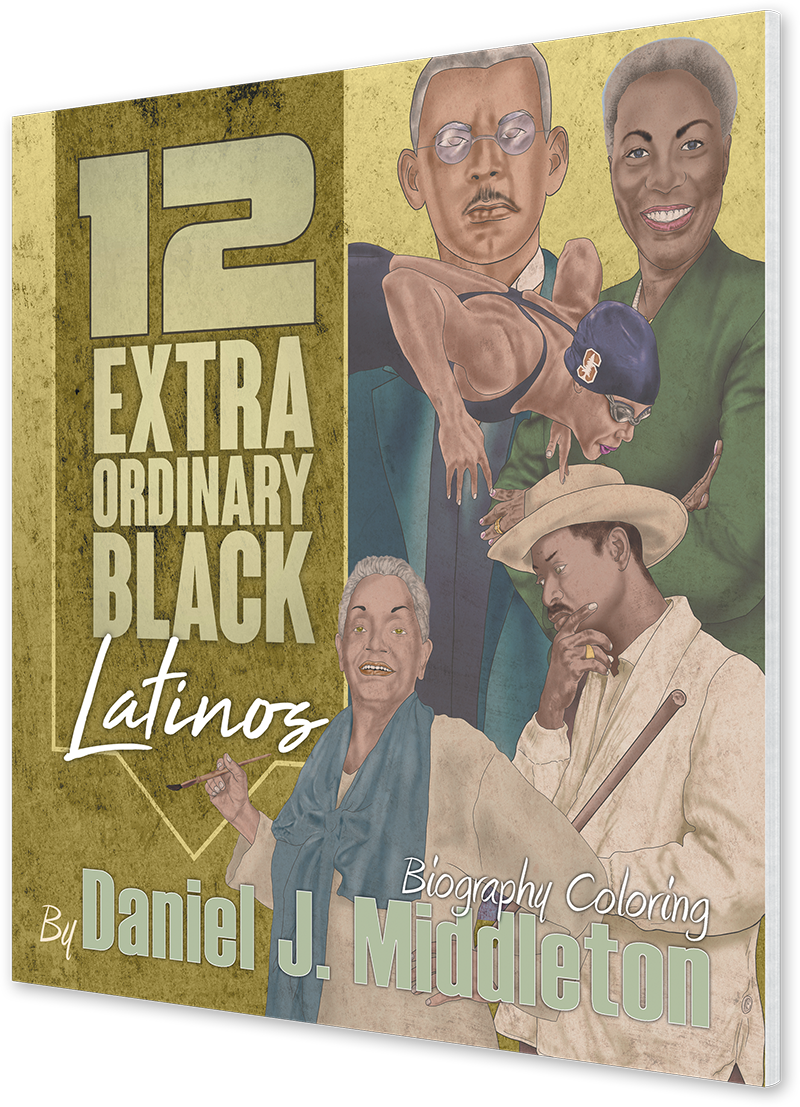

This article appears in 12 Extraordinary Black Latinos.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

As the 28th Secretary of Defense, retired four-star general Lloyd J. Austin III made history by becoming the first black American appointed to that office.