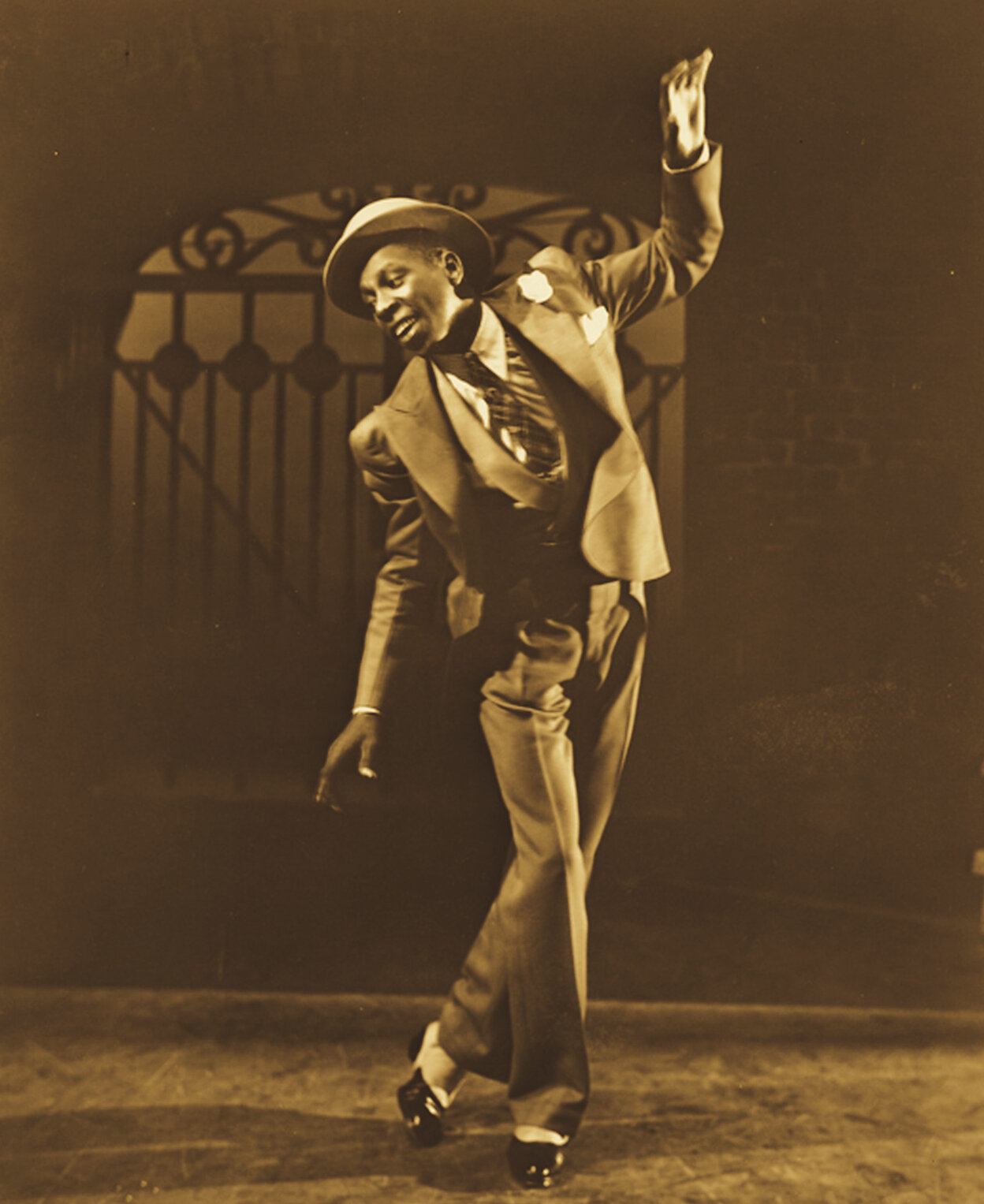

John W. Bubbles

The Father of Rhythm Tap

John W. Bubbles developed a new tap dancing style because he wanted to infuse complexity into the form, and his innovation, which involved dropping the heels at offbeat intervals, was integral to rhythm tap. Born John William Sublett in Louisville, Kentucky in 1902, the nickname “Bubber”—which he altered slightly to “Bubbles”—stuck.

At age seven, Bubbles visited a theater for the very first time and wasn’t impressed. He was so convinced he could sing better than anyone who appeared in the show, he headed backstage and said just that, which earned him a job in entertainment, leading to a lifelong career. He still did odd jobs on the side, as a batboy, stableboy, dishwasher, and peddler of coal, which he hauled using a goat he owned.

At age ten, Bubbles teamed up with another black six-year-old named Ford Lee Washington, whose nickname was “Buck.” Taking the stage name Buck and Bubbles, the two won amateur shows and took their act on the road, performing in Louisville, Detroit, and New York. Bubbles sang and danced with Buck accompanying him while standing at a piano. Bubbles stopped singing at age eighteen when his voice changed, and he focused on dancing.

The new focus did not go well initially. Bubbles won some embarrassment when he was laughed out of the Hoofer’s Club in Harlem for letting his inexperience show. Eddie Rector and Dickie Wells, club veterans in attendance at the time, told Bubbles he was hurting the floor, then they booed the young tap dancer out the door. Bubbles headed west to California and worked on his tap-dancing routine for a year. When he returned to the Hoofer’s Club, no one in the audience dared laugh when he debuted his double over-the-tops and triple back slides. Dancers often stole moves from one another in those days, so necessity forced Bubbles to innovate. In his book, What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing, author Brian Seibert quotes John Bubbles, who once said:

“I didn’t want ’em to copy me, so when I did a show I never did the same step the same way. If I got four shows, I’d do it four different ways … I’d do new steps and I’d do old steps and turn them into something else.”

Buck and Bubbles carried their vaudeville act to new heights, which reached a pinnacle in 1922 when they played the Palace Theatre in New York. Their live comedy act, which included singing and dancing, was so popular the duo headlined white vaudeville shows across the country. This made them a bigger draw than the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA), which was the vaudeville circuit for black entertainers in the 1920s. This was a credit to their manager, acrobat Nat Nazarro, who discovered the two in New York.

“Buck and Bubbles carried their vaudeville act to new heights, which reached a pinnacle in 1922. . . .”

In time, Buck and Bubbles appeared in several Broadway productions, including the 1935 opera Porgy and Bess composed by George Gershwin. Buck and Bubbles made history in other ways too, being the first blacks engaged at Radio City Music Hall (according to the New York Times), and the first to perform at many theaters as they toured the country. Television appearances followed, and the two were among the first black performers to appear in broadcasts in the early days of television. The two appeared in various motion pictures as well, such as Cabin in the Sky (1943), Atlantic City (1944), and A Song is Born (1948). Buck passed away in 1955, and Bubbles was paralyzed after suffering a stroke in 1967. He died in 1996 at age 84.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

One of the most celebrated singers to grace operatic, concert, and recital stages, Jessye Norman was an acclaimed Soprano who weathered the storms of racism to rise to the top of the classical music world.