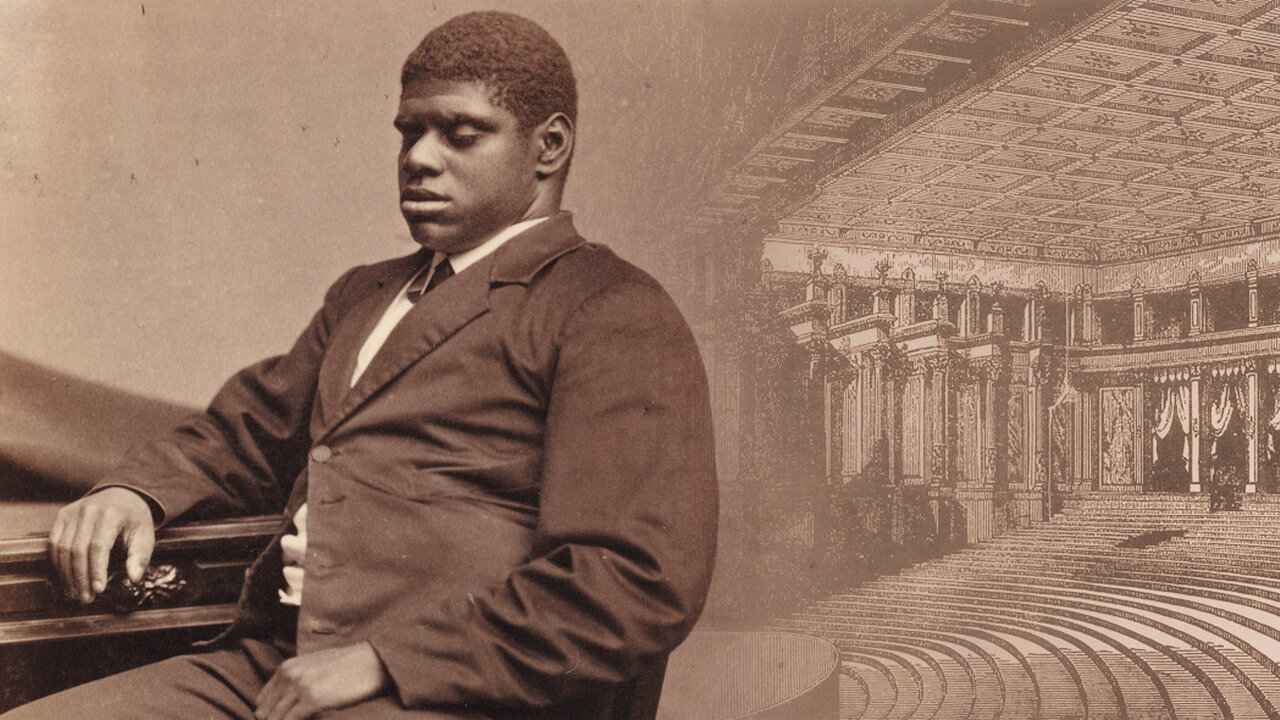

Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins

A Born Slave Turned Piano Virtuoso

Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins seated at his piano. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A slave named Charity struggled to deliver her baby on a Georgia plantation in the spring of 1849. She was 48 years old, and the child born to her on May 25 was a son, who she named Thomas. When Charity discovered that Thomas was blind, it deeply concerned her, and she feared repercussions from her master, Wiley Jones. Jones did despise the child and refused to feed him, but Charity did what she could to preserve his life. Several months later, her family, which totaled five, was sold to pay off some of the debt incurred by her master. Charity pleaded with General James Neil Bethune, who was in the market for slaves, to buy her entire family at auction. Little did Bethune know that by agreeing to do so, he would acquire a tidy fortune.

Charity Wiggins.

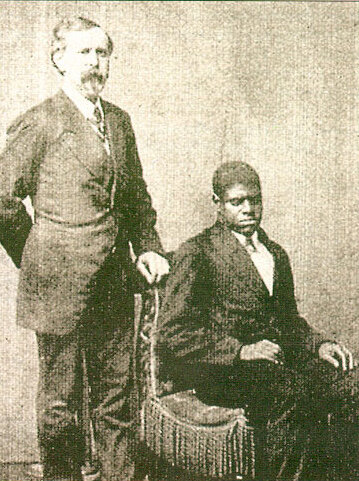

Bethune, a lawyer from Columbus, Georgia, who had become a general during the Creek War of 1832, purchased Charity, her husband Domingo, and Thomas and his two older siblings. The General changed Thomas’s name to Thomas Greene Bethune. There were seven children in the Bethune family who were all musically inclined. Some sang while others played the piano, and during their practice sessions, young Thomas stood by and listened with rapt attention. Thomas’s blindness was not the only thing that made him different. From a young age, he had difficulty walking or expressing himself and therefore communicated with unfamiliar gestures. He was often pugnacious, and some nights he suffered seizures. Thomas could also recall phrases and details he heard in conversation. Today he is thought to have been autistic.

Listening was something Thomas did well. He spent hours listening to everything around him: wind blowing, rain falling on the roof, pots and pans clanging in the kitchen, and many other sounds of life. But the sonatas and minuets the Bethune children rehearsed commanded his attention most. He drew on his talent for memorizing phrases when, at only two years of age, he recited songs in perfect melody he heard sung once by Bethune’s son. Thomas snuck into the parlor at one point, sat at the piano, and played a song he memorized while listening to one of Bethune’s daughters. After a moment, the family rushed in to see who it was. When General Bethune heard Thomas play, he quickly realized he had a piano virtuoso on his hands. Thomas would go on to play piano in a career that spanned almost fifty years.

Bethune arranged for Thomas to have formal piano lessons, but it wasn’t long before the student’s abilities exceeded those of the teacher. Bethune saw his opportunity to create an income stream. The General hired various musicians to play pieces for Thomas to memorize, and before long, the piano prodigy had a complete concert repertoire. At age eight, Thomas gave his first concert to a sellout audience in Columbus, Georgia, which received rave reviews. In 1859, when Thomas was nine or ten years old, General Bethune contracted with a traveling showman named Perry Oliver to feature Thomas for three years, for which Bethune received $15,000. Oliver billed Thomas as “Blind Tom” and kept him to a grueling schedule of four performances a day. In the first year alone, the concerts brought in $100,000 (or more than $3 million when accounting for inflation). That figure ranks him among the highest-paid performers of his day.

Thomas composed around 100 original pieces. Collected here are 14 of them, including his most enduring composition, “Battle of Manassas.” Music performed by John Davis.

Thomas astounded audiences with his gift for mimicry. He imitated his favorite sounds during performances, such as bird calls, the sound of wind, rain, and even locomotives. Thomas often treated his audiences to a rare feat during each performance. He played two songs simultaneously in separate keys with each hand and sang a third without missing a note. Each show included a challenge. Thomas invited a musician from the audience to play a composition he had never heard. Thomas would not only inform the audience of each note played, but he also performed the piece from memory shortly after.

While he could memorize and recite a fifteen-minute long discourse without understanding a single sentence, Thomas could speak a total of about 100 words on his own. Dr. Edward Seguin, a physician who introduced the psychological method, studied the young savant and published his findings in 1866. Despite this limitation, Thomas’s repertoire included more than seven thousand classical pieces and popular songs. He could sing French and German songs after hearing them once. Astonishing abilities such as these brought him before the President of the United States, James Buchanan, at age eleven. They allowed him to perform freely on the stages of opera houses and concert halls throughout Europe and America during celebrated tours. But his mental disorder also left him vulnerable to exploitation by the Bethune family.

Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins and General James Neil Bethune, taken before 1884. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Shortly after the Civil War ended, Bethune arranged for Thomas to remain in his service for another five years. He had his parents (Charity and Domingo) sign a contract to that effect, which entitled them to a modest house and $500 a year. Thomas received only $240 each year and ten percent of the profits from the performances. Bethune kept the bulk. In July 1870, when the contract between Bethune and Thomas’s parents was about to expire, John Bethune—General Bethune’s son—went before a judge to prove Thomas incompetent and, therefore, incapable of managing his affairs. The judge appointed John as his new guardian. The Bethune family enjoyed this new arrangement.

Thomas’s performances continued to earn hundreds of thousands of dollars throughout the years, and John Bethune lived extravagantly as a result. John moved Thomas to a Greenwich Village boarding house in New York City in 1875. A train accident claimed John’s life nine years later, and Thomas’s guardianship was vied for in court by several Bethune family members for three years. John’s estranged wife, Eliza, was the victor, but she still needed to obtain the legal consent of Charity Wiggins. Eliza convinced Charity to make her Thomas’s guardian, and with the deed done, Eliza, who remarried, moved Thomas to Hoboken, New Jersey, and supported herself with his earnings.

Financial problems still plagued Eliza, however, which kept her in court fighting lawsuits. Fearing the income she exploited from Thomas would be seized in court, she locked him away in a New York apartment and even barred Charity from seeing him. Charity expressed her regret to a newspaper reporter before she died in 1902, saying:

“They stole him from me. When I was in New York I signed away my rights. They won’t let Thomas come to see me, and I am not allowed to see him.”

After her final court battle, Eliza allowed Thomas to resume his performances, and he played a few concerts between 1904 and 1906. On June 13, 1908, while in Hoboken, New Jersey, Thomas suffered a stroke that claimed his life. He was 59. So ended the career of the man who concert promoters billed as:

“The Wonder of the World—The Marvel of the Age! The Greatest Living Musician.”

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Roy Eaton broke through the barriers in the advertising industry and rose to become an executive while he composed enduring jingles that resonated with the public.