Bessie Coleman

The First Black Female Pilot Ever!

Bessie Coleman. Photo courtesy of the National Air and Space Museum/Science Source.

In the 1920s, airshows were the rave, but they were dominated by white males. That began to change after a black female decided to get a pilot’s license. And she did this at a time when most men of her own race didn’t have them, partly because they had other things to worry about. A black female earning a pilot’s license at that time would seem impossible today, but Bessie Coleman was able to defy the odds by taking drastic measures during the Roaring Twenties.

Today, people gather to see state-of-the-art aircraft perform dizzying maneuvers at unimaginable speeds. The sound of the planes is sometimes deafening, but audiences don’t seem to mind, since they’re usually gazing up at the sky, mesmerized by the fancy aerial maneuvers of skilled pilots. Back in the 1920s, the planes were less sophisticated, but still quite loud, though audiences didn’t care much about that then either. It was into this dazzling world that Bessie Coleman would be inextricably drawn; the world that eventually gave her the life she dreamed of, and in the end, took her life.

This post contains affiliate links. I may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made through links on this page.

The Birth of Bessie Coleman

She was born Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman in Atlanta, Texas on January 26, 1892, but the family eventually moved to Waxahachie, Texas. The sixth of nine surviving children, Bessie didn’t have it easy from the start. Being born to a large family going through the typical hard times of the era was one thing, but when that family was not only extremely poor but also black, well, that meant living in the grip of fear and worrying about being lynched, on top of everything else.

These were terrible realities for Bessie, but she was blessed with a strong, loving mother named Susan who lived a believer’s life and did her best to encourage her children. Bessie was wise enough to take this encouragement to heart, and she often lost herself in books whenever she could get her hands on them. That was only a few times a year, when the library wagon would come around and allow her to rent a book for a few months for a nominal fee. Among the people she had read about were Harriet Tubman, Booker T. Washington, and Paul Laurence Dunbar, a black novelist, poet, and playwright, all of whom inspired her to reach beyond her present surroundings.

Books and learning in general were important to Bessie. She endured a barefoot, eight-mile roundtrip walk to a one-room schoolhouse to receive her education, and she thought about her books and lessons to and from school. Math seemed to be her specialty, however, because she was good at it. Numbers were her thing.

Her many lessons often ran through her mind while she did laborious field work like picking cotton to help her family. Books were also on her mind when she helped her mother with her laundry business. The bulk of her earnings went to her family, but Bessie was able to save a little here and there, and eventually made it into college. While she soaked up her higher learning, she soon ran out of money and couldn’t afford to attend anymore classes.

Bessie Leaves Texas for Chicago

Undaunted by the setback, Bessie left her Texas home and headed east to Chicago, to stay with her brother John, who had secured employment as a Pullman porter. Bessie found work herself, as a manicurist on Chicago’s South Side. It was 1919. America had recently emerged from a devastating World War and many of its heroes were still recounting events they experienced in Europe. Bessie’s brother John was no different.

He had served in the war as a soldier in the Army, alongside a few brave men. But what he ribbed Bessie about was the fact that over in France, women had many opportunities. They were liberated souls, and they even flew planes. John teased Bessie about her job as a manicurist and told her she and other black women like her “ain’t never goin’ to fly, not like those women I saw in France.” At least that’s what he’s quoted as saying in the 1993 biography Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator by Doris L. Rich.

Coleman is said to have responded: “That’s it!” with a cool smile. “You just called it for me.” That could only mean one thing: Bessie had to prove her brother wrong. She set out to do so by reaching out to several male pilots, who she hoped would take her on as a student. None did. America was still in a very racist period after all, and beyond that, women of any race were still denied basic rights.

Coleman was reminded of those wonderful European opportunities her brother spoke of, so after a little research, which assured her that flight schools abroad accepted students regardless of race or gender, she planned on sailing to France to explore those opportunities she’d heard about.

Bessie Sails to Europe

The prominent publisher of a black newspaper called the Chicago Defender got wind of Bessie’s plans. His name was Robert S. Abbott, and to him, considering what a boon Bessie’s achievements would be to blacks in America, encouraging her toward her goal simply made sense. Abbott convinced Bessie to learn French, which she did by taking language classes, with his support.

In fact, Abbott believed in Bessie so much that he even helped finance her voyage to France. After landing a better paying job managing a chili restaurant, she was able to use more savings toward her trip. Bessie set sail for Europe on November 20, 1920, aboard the ocean liner SS Imperator, which for her must have been a breathtaking experience.

Upon arriving in France, Bessie headed north and enrolled at the flight school of the famous Caudron brothers, who were pioneers of aviation at the time. Bessie embarked on a seven-month training course, during which she learned to fly a rickety Nieuport Type 82 biplane. The aircraft was 27 feet in length with a wingspan that topped that at 40 feet. But the plane was a relic. Bessie made sure to inspect it carefully prior to each flight for her own safety.

The plane didn’t even have a proper steering wheel or brakes. The pilot had to use a makeshift wooden joystick to maneuver the plane. A metal skid attached to the tail simply dragged on the ground during landing to act as the brake. Despite the plane’s poor condition, Bessie did learn several key maneuvers during her training, such as loop-the-loops, tailspins, and banking, which impressed her French instructors. But Bessie saw a fellow student plunge to their death during a training accident. She later expressed that while the event shook her nerves, she never lost them. She just kept going.

Bessie Coleman Becomes the First Black Female Pilot

Finally, on June 15, 1921, Bessie Coleman made history by being awarded a pilot’s license from the French International Aeronautical Federation, being the first black female to do so. In fact, the more famous female pilot of another race, Amelia Earhart, would not earn her license for another two years. With her newly earned pilot’s license, Bessie could fly anyplace on earth; it was her right. Of course, that meant a trip back to the states.

When Bessie arrived in New York, the Associated Press hailed her as “a full-fledged aviatrix.” To add to her flight repertoire, Bessie returned to Europe to receive advanced training in France, Holland, Switzerland, and Germany. This increased her skills and left her satisfied enough to return to America with a new dream: that of opening a flight school for blacks, both men and women. She felt deeply for her race, and wasn’t shy about sharing those emotions. “I shall never be satisfied until we have men of the Race who can fly,” wrote the Chicago Defender in 1921, quoting her. She added:

“We must have aviators if we are to keep pace with the times.”

In Bessie’s mind, there was no better way to make her dream come true than to use her newfound flight skills to raise the needed capital to launch her new enterprise. So, she borrowed a plane and went barnstorming across America in 1922, dazzling crowds with tricky aerial maneuvers and even walking on the wing of her plane. She also parachuted while a co-pilot took the bird in for a landing.

Newspapers—particularly the ones aimed at black readers—ate it up. Coleman became a sensation, yet she insisted that each time she flew in a show, the audience had to be integrated and blacks must be allowed to enter through the same gates as whites. Bessie also gave motivational speeches at black churches and schools, encouraging her people to follow their dreams and pursue their life goals.

Bessie’s Final Days

But her main line of work was extremely dangerous, considering the sad state of the old planes she borrowed. Even putting up her own funds to purchase a used Curtiss JN-4, otherwise known as a Jenny, didn’t improve matters. While in Florida to do an air show, Bessie and her mechanic, William D. Wills, flew up to scout the surroundings in preparation for the next day’s main event. Wills, her white co-pilot, flew the plane while Bessie took a look around in the rear cockpit, unharnessed so she could get views of good landing spots for parachuting.

Everything went smoothly at first, with Wills flying at 2,000 feet for a few brief minutes. But when he climbed to 3,500 feet, witnesses on the ground said that the plane took a steep nosedive after a sudden acceleration. Then they went into an unplanned tailspin that flipped the plane upside-down, which sent poor Bessie flying from the cockpit. She fell to her death at the age of 34, and Wills crashed the plane, dying on impact as well.

A subsequent investigation revealed that a loose wrench jammed up the control gears, making the efforts of the pilot useless. Also, when rescuers arrived at the scene of the crash, they found Wills pinned under the wreckage and tried to free him. As they worked, one of the rescuers took a smoke break, lit a match, and ignited the gasoline fumes that hung in the air, causing flames to rage from the wreckage.

White newspapers hardly mentioned Bessie Coleman’s passing, instead focusing on Wills and his tragic end. But black newspapers placed her on the front page. About 10,000 people came out to mourn Bessie’s passing. She lay in state in Florida and Chicago and was interred at Chicago’s Lincoln Cemetery, but her dream of opening a flight school for blacks did not die with her. Lieutenant William J. Powell opened the first one in her honor, naming it The Bessie Coleman Aero Club. Powell later wrote in his book Black Wings:

“Because of Bessie Coleman, we have overcome that which was worse than racial barriers. We have overcome the barriers within ourselves and dared to dream.”

Bessie’s legacy also impacted another generation, the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II, America’s elite pilots who were the first blacks to earn their wings in the U.S. Armed Forces. Today, Bessie is not only remembered and honored among blacks, but by people of many races. She still inspires those who dream to reach higher and farther than they currently are, just as she did.

You may also be interested in:

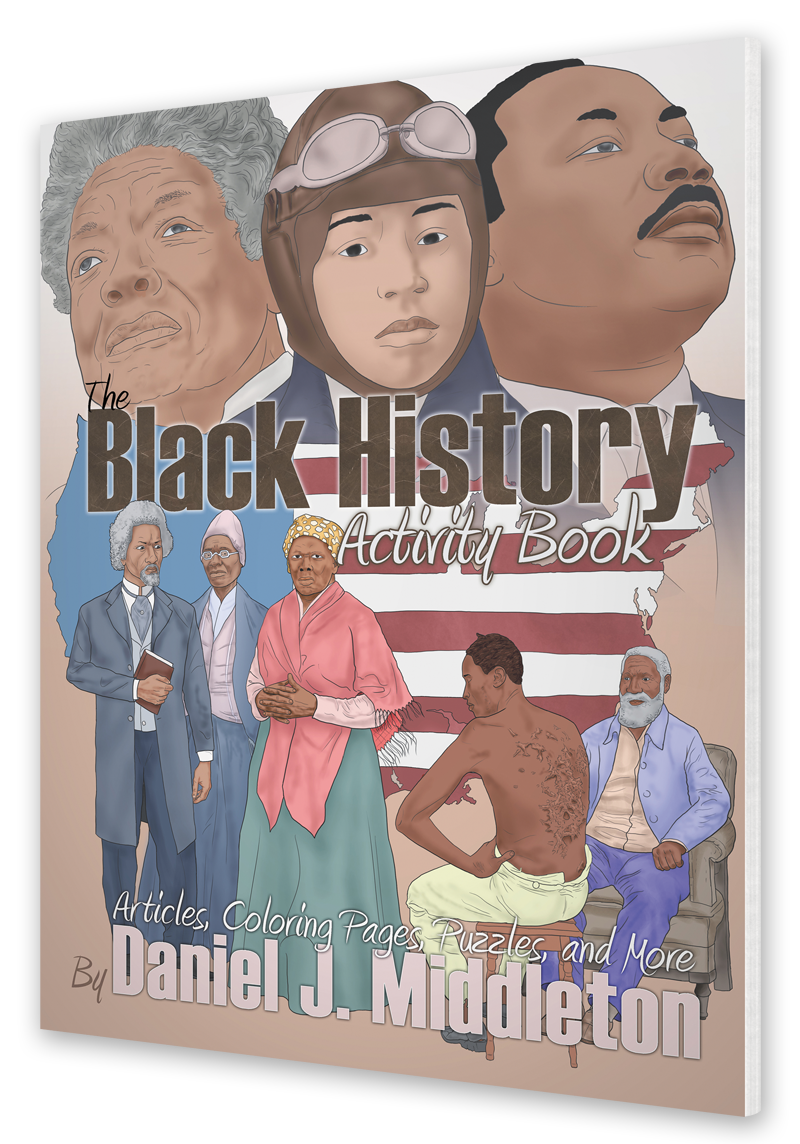

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Esteban Hotesse served in the U.S. Armed Forces in the 619th Squadron of the 477th Bombardment Group. That made him the only Afro-Latino member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen.