Freedom House Ambulance Service

The First Fully-Trained Paramedics

In the 1950s, funeral homes ran privatized ambulance services, as there were no hospital-supplied ambulatory units at the time. Paramedics training was also nonexistent, so there was no emergency care in the field. Police wagons and funeral hearses transported patients to hospitals, where medical treatment would begin.¹ Prehospital emergency medicine was unheard of even in the early 1960s. In Pittsburgh, the privatized ambulance services—as limited as they were—mainly serviced suburban whites, or people living in affluent neighborhoods. Blacks living in the Hill District who needed medical care received rough treatment during transport to hospitals by police wagon. From this predominantly black district, emergency medical services emerged, with black paramedics paving the way for modern EMS standards throughout the world.

The year 1966 was a low ebb for blacks living in communities like the Hill District, where unemployment was rampant. And not only was social services absent, but there was either a delay in or severe lack of needed medical care in the black community. Phil Hallen and James McCoy were two activists who saw a dire need in this area and advocated for change. Phil Hallen was a former hearse-style ambulance driver and later a member of the Pittsburgh Hospital Planning Association. He witnessed the inadequate medical response of the city during this time. It relied on outdated technology and untrained and ill-equipped police officers to transport patients during medical emergencies. He later stated:

“I came to Pittsburgh and saw things that were 25 years behind the times. They were using police vans and canvas stretchers ... and the white-owned funeral homes didn't want to go near what we used to call ‘the ghetto.’ ”

When Hallen was on the Hospital Planning Association, Pittsburgh hospitals had since discontinued their ambulance services. No budget existed to reverse the situation either. Hallen, however, was later named president of a local charity called the Maurice Falk Medical Fund. The foundation was flush with community program cash. The opportunity to revolutionize emergency transport, therefore, was on the horizon. That opportunity came toward the end of the year, on November 4, 1966. David Lawrence, the 37th governor of Pennsylvania and the celebrated mayor of Pittsburgh, from 1946 to 1959, became a catalyst for reform of the city’s local emergency services, though hardly a willing one.

On that ominous date, David Lawrence gave an enthusiastic speech to an audience at Pittsburgh’s Syria Mosque in support of gubernatorial candidate Milton Shapp. His speech was so spirited in fact that Lawrence collapsed after suffering a massive heart attack. An experienced nurse happened to be in the audience, and she rushed to Lawrence’s side to administer CPR on the spot until a police wagon pulled up.

Two officers rushed inside, threw Lawrence onto a canvas stretcher, and raced him to their emergency vehicle while the nurse tried to keep pace. All she could do was watch as Lawrence suffered respiratory arrest. When she climbed into the back of the wagon with her patient, she found a broken resuscitator, a mark of the budget-strapped and inefficient ambulance service. A rough ride to the hospital ensued, with Lawrence and the nurse swaying with the vehicle’s movement so violently that resuscitation efforts ceased. The flow of needed oxygen to Lawrence’s brain stopped during the crucial minutes it took to reach the area hospital. He was finally resuscitated upon arrival but suffered permanent brain damage and never regained consciousness in the time between his rush to the hospital and his death some two weeks later.

This event, which was magnified by the publicity that unfolded, spurred Phil Hallen into action. Lawrence’s death—coupled with local initiatives to bring businesses to black communities—inspired Hallen to draft his “Preliminary Thoughts on the Development of a Private Ambulance Service in the Hill District” in February 1967, which became the blueprint for the first exhaustive paramedic service staffed by civilians. And Hallen knew that Pittsburgh’s Hill District was in sore need of such a service. What better place was there from which to draw residents for training and employment to serve their community? There was a need for managers, ambulance crews, and clerks, who could eventually move into other areas of the medical field with experience on the job.

But an enterprise along this line required serious backing, so Hallen took his proposal to the president of University Hospital. There was enough promise in the idea to prompt the hospital president to refer Hallen to a more suitable medical ally: Dr. Peter Safar. A pioneer in his own right, Safar is noted for developing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. The American Heart Association adopted it for official training. Safar also established the nation’s first intensive-care unit (ICU) at Baltimore City Hospital in 1958. That achievement extended to the first intensive-care medicine program at the University of Pittsburgh. When Safar heard of Hallen’s proposal, he saw it as a means of furthering his ideas on emergency care beyond the walls of the hospital and happily came aboard.

“He was a man of considerable social conscience and in a sense, it was a bonus for him,” Hallen later said of Dr. Safar. “I mean he could have trained anybody. But he saw the value of demonstrating this in a population of individuals who hadn’t been thought of as having that kind of potential.”

Since all of this was unfolding in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, it seemed logical to involve a prominent community figure dedicated to improving life in the black community. Enter James McCoy, Jr., head of Freedom House Enterprises (FHE), a nonprofit organization with funding from the federal government’s War on Poverty initiative. The FHE had been instrumental in securing training and employment for blacks as hairdressers and truck drivers. But Hallen suggested that McCoy should focus on training them to drive ambulances instead.

Hallen’s ambitious proposal attracted other prominent figures, and, with adequate support and funding in place, recruitment efforts were soon underway. Freedom House established its base in Presbyterian-University Hospital’s Emergency Room. While its founders envisioned a fleet of ambulances for the new service, the city supplied just two used police wagons. Freedom House’s operating budget, meanwhile, was a paltry sum for such an enterprise. Of the 25 blacks who entered the training program in October 1967, 20 graduated from the first section and were allowed to continue their training on-the-job in the next nine months. A $100,000 city contract earmarked for ambulance services to Pittsburgh’s Downtown area and Hill District made this possible.

The trainees were not quite ready when riots broke out in Pittsburgh in April 1968, in part because their ambulances were still in the design phase. The city still had to act, but since its resources were low, and Freedom House members were the only ones in Pittsburgh with proper emergency training, city officials decided to assign these blacks to ride with police, two paramedics per wagon. Freedom House’s first run at providing emergency care in the field proved successful. Following the riots, the paramedics returned to training, which continued throughout Freedom House’s existence since the ambulance service operated within a hospital, unlike the police, firefighters, and privatized funeral homes.

“Nowhere else in the nation was this level of medical service provided outside of hospital settings.”

Freedom House paramedics responded to more than 5,600 calls in the first year, mostly in black districts. Of those, more than 4,800 patients received emergency care while being transported to the hospital. In its seven years, the calls would balloon to over 40,000. Nowhere else in the nation was this level of medical service provided outside of hospital settings. In time, things also improved slightly on the budget front, thanks to new grant funding in 1973. This funding allowed Freedom House to obtain signature orange-and-white ambulances decked with advanced life support equipment that included suction units, defibrillators, and the like.

In another year, Freedom House extended its services into other Pittsburgh neighborhoods, where black paramedics experienced racism. With the new funding, staff diversification occurred. Dr. Safar hired the last of the notable figures to shape Freedom House in 1974. Her name was Nancy Caroline, who had arrived in Pittsburgh the year before to complete her residency in a program focused on critical care medicine, which was developed by Safar. He assigned Nancy Caroline as medical director of Freedom House, and she soon grew impassioned with the service. It became her life, and she devoted so much time to teaching, mentoring, riding with crews, and seeking the overall improvement of Freedom House that she was known to sleep on stretchers at the station during shifts. She was instrumental in securing another grant from the Department of Transportation, and she authored a widely used paramedic textbook, Emergency Care in the Streets. Two years after that, a paramedics training manual followed.

In the end, all the support Freedom House enjoyed over the years was not enough. Despite its grants and the clinical leadership that helped shape the service, the winds of change stirred in the mid-1970s. The city assumed control of Freedom House, and institutional racism destroyed the fabric of the old order. Freedom House was disbanded in 1975 and replaced with an ambulance service run by the city.² The city hired new doctors who altered the original protocols. Under the new rules, they fired black paramedics with criminal records, while they passed over others for promotion despite many having at least eight years of experience. Those elevated positions and salary increases went to inexperienced suburban white men instead. The only partial exception was a black Freedom House pioneer named John Moon. He rose through the ranks to assistant chief of the city’s paramedic service. But they never promoted him to the top spot, despite his obvious qualification.

Freedom House employed the world’s first fully-trained paramedics. These blacks managed to influence the development of EMS across the nation. Though it was short-lived, Freedom House provided such a high level of medical treatment in the streets, other cities followed suit and carried their efforts far beyond Pittsburgh. And the future of EMS is still being built on the foundation of their achievements.

____________________

Learn more about Freedom House, and the history of emergency medical care, by reading The Ambulance: A History.

You may also be interested in:

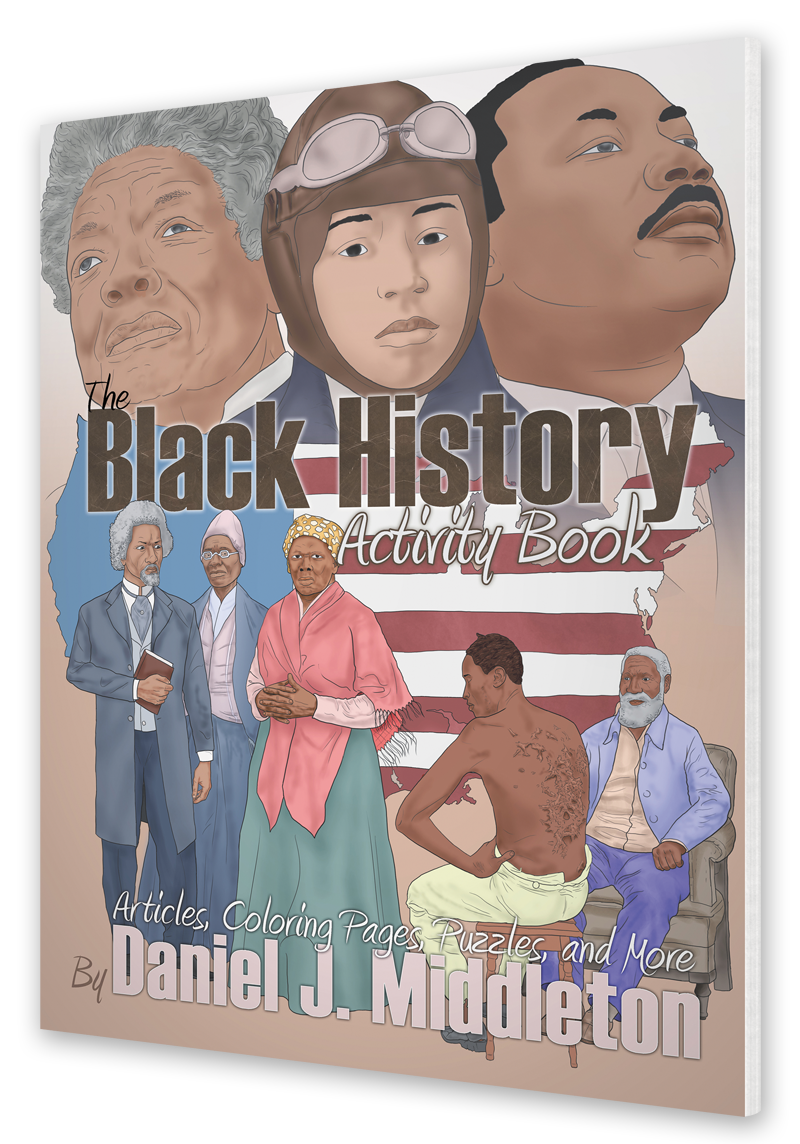

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

With segregation at its height, and New York City blacks being pushed farther uptown from the Lower East Side, mortality rates soared and illnesses plagued their communities. That is when a registered nurse named Elizabeth Tyler decided to act.