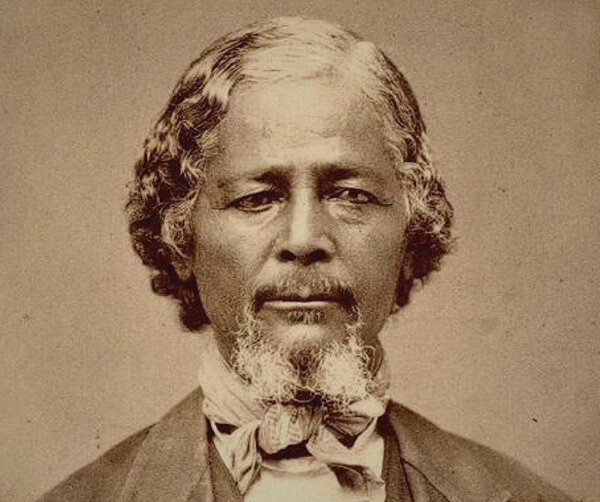

Martin Delany

The Father of Black Nationalism

Portrait of Martin Delany.

Martin Delany, though little known to the world today, is a towering figure in American history. In addition to being an abolitionist, whose life was consumed with efforts to end slavery, Delany was also an author, newspaper editor, physician, and the first black field officer in the Union Army. He was also among the first three black men to enter Harvard Medical School. A friend of fellow abolitionist Frederick Douglass, Delany succeeded where Douglass had failed.

Douglass had approached President Abraham Lincoln with a proposal to use black troops in the war against the South, with the idea that he would lead them into battle. Lincoln turned him down. But as the Civil War progressed, Lincoln’s views on the recruitment of black soldiers shifted. By 1863, Martin Delany was recruiting black men across New England to serve in the newly formed and segregated 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Two years later, he persuaded the president to commission black officers to lead black troops into battle. To that end, Delany was commissioned as a major.

Martin Robinson Delany was born a free man in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia) on May 6, 1812. His father, Samuel Delany, was a slave whose trade was carpentry, but his mother, Pati Peace, was a free woman who worked as a seamstress. In 1867, Delany recounted his life story to author Frances A. Rollin for a planned biography. The book that emerged was Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany. In it, Rollin reports that all of Delany’s grandparents were Africans, a fact he was extremely proud of. Delany’s grandparents on his father’s side were pure Gola — a people who inhabited what is Liberia today. Captured in warfare, they were shipped to the Virginia colony as slaves, but his grandfather, who was reportedly a former village chieftain, escaped to Canada for a time.

His grandparents on his mother’s side were reportedly Mandingo, whom the author says were nicknamed “the Jews of Africa.” Delany’s paternal grandfather was reportedly a prince among them. His name was Shango, and he was also captured during tribal warfare and sent to America with Graci, his betrothed. But, Frances A. Rollin reports:

“Shango, at an early period of his servitude in America, regained his liberty, and returned to Africa.”

Graci, on the other hand, remained stateside after being granted the same freedom, and she lived with her daughter Pati until her death at the age of 107. Given his deep-rooted African heritage, Delany longed to return to his ancestral homeland. He would not see the continent until he reached manhood. As a young boy, he enjoyed the protection and nurturing of his mother, Pati. When attempts were made to enslave both Delany and a sibling, Pati hauled the two children to a courthouse 20 miles away in Winchester, where she successfully argued for their freedom on the grounds of her own, seeing she was born a free woman. Pati also taught her children to read and write using The New York Primer and Spelling Book, which they received from a peddler. But this practice was against Virginia law at the time, as blacks were not allowed to receive education.

When it was discovered that Pati had been teaching her children to read, she was issued a summons to appear in court. She knew that this would result in a severe penalty, as it was a crime for which even a white woman — Connecticut teacher Prudence Crandall — was arrested and jailed.¹ Pati was persecuted by white Virginians for the offense, but one kind banker, Randall Brown, offered her good advice: he told her to leave town. In September of 1822, Pati did just that. She packed up their belongings and, with her children in tow, gave the false impression that she was leaving Charles Town for Martinsburg, Pennsylvania, but instead headed to Chambersburg located about 50 miles farther north. The free state of Pennsylvania allowed Pati to teach her children in peace, and she even sent them to school. She remained in Chambersburg for fifteen years, and it was there that her husband, Samuel, reunited with the family once he bought his freedom.

While in Chambersburg, Delany continued to study, but as he grew older, his parents could not afford to continue sending him to school, so he went away on occasion to find work. The longest and most arduous of his journeys — and the one for which he sought special permission from his parents — took him 160 miles to Pittsburgh in 1831. He started out on July 29th, traveling on foot with little to no money. When he crossed the three grand ranges of the Alleghenies, he reached the small frontier town of Bedford, on the edge of the wilderness, where he found employment. Delany remained in the town for a month before moving on. He kept his eyes fixed on Pittsburgh, “in which city the foundation of his fame afterwards rested,” wrote his biographer, Frances A. Rollin.

“The longest and most arduous of his journeys … took him 160 miles to Pittsburgh in 1831. He started out on July 29th, traveling on foot with little to no money.”

Once in Pittsburgh, he worked as a laborer and barber to earn enough to live on and continue his studies. He eventually enrolled as a student of Reverend Lewis Woodson, a black separatist who operated a school for blacks in Bethel AME Church. The church was also the setting where Delany and community leaders like John B. Vashon and others held literary and political discussions. Of this, Robert S. Levine, author of Martin R. Delany: A Documentary Reader, writes:

“From those discussions emerged the African Education Society, which proclaimed in its constitution ‘that ignorance is the sole cause of the present degradation and bondage of the people of color in these United States; that the intellectual capacity of the black man is equal to that of the white, and that he is equally susceptible of improvement.’”

Later, Delany attended Jefferson College, where he studied Latin, Greek, and the classics. In 1833, during a severe cholera epidemic that swept through Pittsburgh, Delany learned medicine as an apprentice to several abolitionist doctors, whom he served by cupping and leeching patients — this was a primary technique for treating diseases at the time.

It was in this period that Delany also engaged in abolitionist activities. In addition to aiding in the formation of the Pittsburgh Anti-Slavery Society, he was secretary to the executive of the Philanthropic Society, which was merely a cover organization that rescued, protected, and transported fugitive slaves through Pittsburgh. But Delany made no secret of his other abolitionist efforts. The Colored American, the most influential black newspaper in circulation in that period, ran notices that detailed Delany’s activities. And with the knowledge he gained as an apprentice to various local physicians, Delany opened his own office and became a private cupper and leecher. Money earned from this medical venture financed his abolitionist efforts, and helped to establish him as a civil rights leader.

In August of 1841, Delany attended the State Convention of the Colored Freemen of Pennsylvania, which he helped organize. During the convention, the black delegates unanimously approved Resolution 11, which called for the creation of a newspaper run by blacks and completely devoted to the issues of black people.² After waiting two years for such a paper to materialize, Delany took matters into his own hands. He began publishing a four-page paper called The Mystery in September, 1843. The paper, which Delany wrote and edited, centered on antislavery issues, and the advancement of blacks. In it he ran letters and editorials, and announced various events and meetings taking place in the area. He also ran advertisements for black Pittsburgh laborers and business owners.

Delany met Catherine A. Richards while living in Pittsburgh, and they were married in 1843, the year he launched his paper. Catherine’s father was a successful food provisioner who was said to be wealthy. In time, the couple had 11 children, but only seven survived to adulthood. During the five years he ran his paper, Delany kept writing and publishing, but his antislavery coverage eventually landed him in trouble. In 1846, he was sued for libel by Thomas “Fiddler” Johnson, a black man he accused of being a slave catcher. A white jury found Delany guilty, but the heavy fine he incurred was later remitted by the governor. Following the lawsuit, Delany sold his interest in the paper, which was renamed The Christian Recorder, but he did not quit the newspaper business altogether. His success with The Mystery led to another publication. Frederick Douglass traveled to Pittsburgh in 1847 on an antislavery tour. Accompanying him was William Lloyd Garrison, a white abolitionist, journalist, and editor who often reprinted Delany’s articles in his own paper, The Liberator.

Delany joined forces with Douglass and Garrison (with whom Douglass later broke off his friendship), and together they launched a new four-page paper called The North Star. It enjoyed a circulation of 4,000, with subscribers in the United States, Europe, and the West Indies. In fact, it became the most influential black antislavery newspaper of the pre-Civil War period. Named for the North Star seen in the night sky, which runaway slaves used as a guide to make their way to freedom, the paper was co-edited by Douglass and Delany and was published in Rochester, New York. While the two did not always agree, both men personally financed the paper for a time, until their resources were drained. At that point, Delany ended his partnership and returned to the medical field by reopening his cupping and leeching practice. He also pursued formal medical studies in order to advance his career, but that valiant effort met with great opposition. Of this period, Levine writes:

“Delany attended Harvard Medical School for several months but was dismissed because of his color. Outraged by Harvard’s racism and the Compromise of 1850, in 1852 he published The Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States.”

It was a book-length treatise that criticized the United States for failing to grant equal rights to blacks, and which ended with Delany calling for black people to emigrate en masse and establish a new nation elsewhere, such as in the West Indies, or Central and South America. He would later shift his focus to West Africa for such an enterprise, following an exploratory journey to that part of the continent in 1859. There, he hoped to set up a “black Israel.” A few years prior to that, Delany helped to organize a convention related to the subject of emigration. It was held in Cleveland, Ohio, and the gathered delegates (over a hundred in number) elected him president pro tem.

In 1856, Delany moved his family to Chatham in Ontario, Canada, where he resumed his medical practice. Two years later, he organized the African Civilization Society and spent a year traversing central Africa’s Niger Valley in search of a suitable site for his emigration enterprise. Upon his return to Canada, he was filled with a new zeal, with his heart and aims centered on Africa. But the United States was on the brink of Civil War, and Delany felt the pull of duty to his fellow black countrymen. This drew him back to U.S. soil. In his book, The Negro’s Civil War, author James M. McPherson says of this phase in Delany’s life:

“In January 1863 the War Department authorized Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts to raise a regiment of Negro soldiers in his state. Massachusetts’ Negro population was too small to fill up a regiment, so Andrew called upon the wealthy abolitionist George L. Stearns to form a committee of ‘prominent citizens’ to raise money for the recruitment of men for the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment from all over the North. Stearns hired several Negro leaders as recruiting agents.”

Among them was Martin Delany. His son, Toussaint L’Ouverture Delany — named for the leader of the Haitian Revolution — also signed on to fight with the first colored regiment formed in the North, that being the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. The ravages of war exacted their heavy toll as time passed, and by 1865, Delany moved his family to Wilberforce, Ohio. That year he was also commissioned as major of the 104th U.S. Colored Infantry by President Lincoln. After Lincoln met with Delany, the president reportedly wrote to his Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, that Delany was, “a most extraordinary and intelligent man.” While the commission made Delany the highest-ranking black officer to lead troops, the Civil War ended before he led them in actual combat.

Delany was then posted to Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, where he worked with the Freedman’s Bureau, the government agency that helped former slaves adjust to post-slavery life. Around this time, Delany, ever the black advocate, shocked his white superiors by declaring that those ex-slaves had a right to own land. He was mustered out of the Freedman’s Bureau and later retired from the army, but he remained in South Carolina, where his family joined him. They lived there for a considerable portion of his remaining life, during which he was politically active in the state. Delany ran for the South Carolina lieutenant governor seat as an Independent Republican but lost. He also served as a trial justice.

Indeed, Martin Delany was many things, but foremost he was proud of his race, regardless of their struggles, and despite the oppression they endured in a country that failed to see them as citizens. His love for his people was evident in his espousal of black nationalism, which was his driving force. His zeal for the black cause, coupled with his brutal criticism of the United States and many of its institutions have tarnished his legacy, leaving others like Frederick Douglass leagues ahead of him in terms of historical prominence. But Martin Delany — say what you will of him — left a sizable footprint in the sands of history.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Ida B. Wells was an unsung early civil rights leader, suffragist, researcher, and journalist who used her pen in ways that are yet to be rivaled.