Freedom’s Journal

The First Black-Owned and Operated Newspaper in U.S. History

Samuel E. Cornish and John B. Russwurm, founders of Freedom’s Journal, the first black newspaper in the U.S. Images courtesy of the Los Angeles Sentinel.

Until the early nineteenth century, the mention of blacks in white mainstream newspapers was often connected with a crime. That state of affairs was challenged on March 16, 1827, when a four-page, four-column weekly newspaper was established. And this was no ordinary paper. Freedom’s Journal, as it was called, was the first black-owned and operated newspaper in U.S. history. The year it came into being, slavery was officially abolished in the state of New York.

This change allowed a group of free black New York residents to give voice to a reform movement that was opposed to the dominant racist views of the white press. Out of this group, a Presbyterian minister named Samuel E. Cornish was the senior editor and John Brown Russwurm, an early black college graduate, served as the junior editor. Freedom’s Journal was circulated across 11 states, as well as the District of Columbia, Canada, Haiti, and Europe.

Samuel Cornish resigned as editor six months after the paper’s launch, leaving John Russwurm as sole editor. They had fallen out over the issue of black colonization, an agenda Russwurm was bent on pushing and which Cornish was against. Among the topics covered in Freedom’s Journal were: current events, world news, anti-slavery and anti-lynching editorials, broad injustices, biographies of important black figures, and a record of marriages, births, and deaths in the black community of New York City. Freedom’s Journal also ran ads that cost between 25 and 75 cents.

View of South Street, from Maiden Lane in New York City, ca. 1827. Painted by British artist William James Bennett. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The paper lasted from 1827 to 1829, spanning 103 issues in two volumes.¹ As a result of Freedom’s Journal, more than 300,000 black Northerners had access to knowledge of world events and current issues that directly impacted blacks. The biographies of notable black figures acted as a means of racial upliftment. Readers were lavished with features such as the one on the affluent shipping magnate Paul Cuffee, a black Quaker who employed black workers and advocated for the colonization and emigration of blacks to Africa.

Aside from the editors and staff, the paper dispatched sometimes dozens of hired agents to handle subscriptions, which was $3 per year. One such agent was a man named David Walker, who created quite a stir when, in 1829, he penned the first of four antislavery articles that called for slave resistance. In it Walker argued:

“It is no more harm for you to kill the man who is trying to kill you than it is for you to take a drink of water.”

As a hired agent, Walker personally distributed the paper containing his appeal throughout the South, where it was largely banned. With Samuel Cornish’s departure in 1827, Freedom’s Journal adopted a softer tone and became increasingly pro-colonization, as its sole editor John Russwurm, in support of a predominantly white organization called the American Colonization Society, repeatedly argued for the repatriation of blacks to the continent of Africa. Readers largely rejected this view and, as a result, sales suffered. Russwurm published the last issue of Freedom’s Journal on March 28, 1829.

Holding firm to his beliefs on repatriation, he moved to Liberia and launched another paper called the Liberia Herald. Samuel Cornish made a brief return to the newspaper business in May of 1829 as well, when he resurrected Freedom’s Journal under the title The Rights of All. That publication lasted for several months and soon disappeared. While Freedom’s Journal only ran for two years, its influence was far-reaching, and it acted as a model for no less than 40 black abolitionist newspapers that arose throughout the U.S. after its closure and before the Civil War.

You may also be interested in:

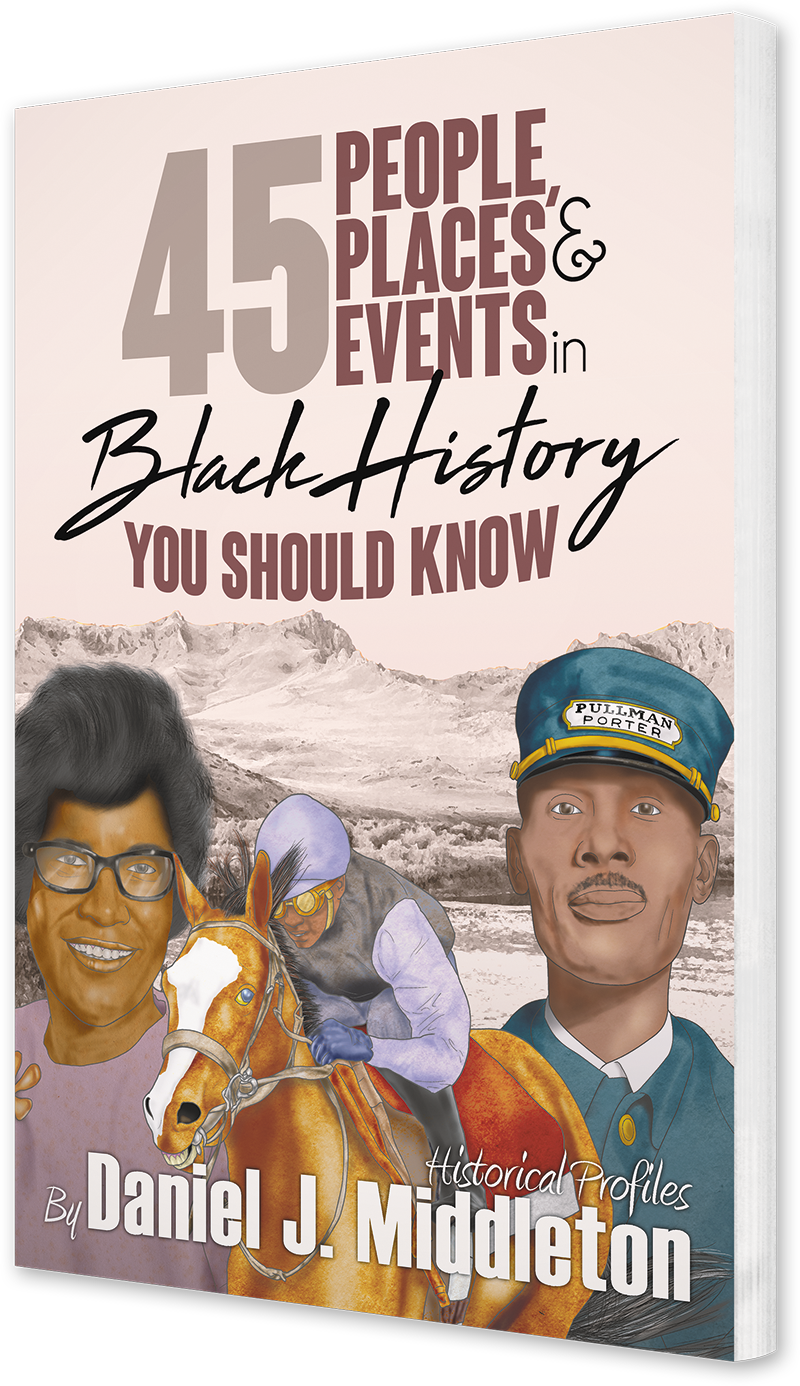

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Dorothy Brunson owned three radio stations and pioneered what came to be known as urban contemporary radio. She was also the first black woman to own and operate a television station.