Ida B. Wells

The Groundbreaking Early Civil Rights Leader

Ida B. Wells was a prominent journalist, editor, and co-owner of two black newspapers, and she used the power of print to expose the severity of discrimination and racial inequality experienced by blacks in America. She also denounced lynchings, actively fought for women’s rights, and defied the bigotry and oppressive racism of her time with every fiber of her five-foot frame.

Ida was born into slavery on July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi during the Civil War. Her parents were James and Lizzy Wells, both of whom belonged to the Republican Party and were active in politics during Reconstruction. Ida’s father was a member of the Freedman’s Aid Society, and with them, he helped start a liberal arts school for newly freed slaves called Shaw University (the name later changed to Rust College to distinguish it from the Raleigh, NC school of the same name). James Wells was one of the school’s first trustees. Rust College is one of only 10 Historically Black Colleges and Universities established before 1869 that are still active.

Ida received her early education at Rust College but was forced to drop out when she was 16. She was orphaned at that age due to a yellow fever epidemic that claimed the lives of her parents and infant brother. She later headed to a nearby school and convinced the administrator she was 18 to work as a teacher and support her five remaining siblings. But it was when she moved to Memphis with her younger sisters that her career as a journalist and civil rights activist began. Her brothers were able to secure work as apprentices to carpenters and set out on their own.

Ida continued working as a teacher in Memphis for a time while taking classes at Fisk University in Nashville to further her education. At age 21, Ida intended to travel to Nashville as usual and purchased a first-class train ticket. But she was confronted by the conductor who ordered her to move to the less accommodating area of the train designated for blacks, despite her ticket purchase. When Ida refused, the conductor attempted to drag her out of her seat by force, and so she “fastened [her] teeth on the back of his hand,” as she later wrote.

“[T]he conductor attempted to drag her out of her seat by force, and so she “fastened [her] teeth on the back of his hand.’ ”

Ida was awarded a $500 settlement after suing the railroad in circuit court, but the Tennessee Supreme Court later overturned the decision. It was this action that sparked the activist fervor in Ida B. Wells. Though she worked as a teacher in a segregated Memphis school, she began to write on the side. Her unsparing pen was soon criticizing the poor condition of black-only schools in the city. In 1891, she was fired for her brutal honesty.

The next year, a friend named Tom Moss, who owned a grocery store in Memphis, was lynched, along with co-owners Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart. The black-owned store, The People’s Grocery, was in direct competition with the white-owned store in the neighborhood and was considered to be stealing business. The jealous white rival gathered supporters and confronted Moss and his partners on several occasions until things came to a head. While Moss and a few associates were guarding the store one night, a few whites attempted to vandalize the black grocery and several of them were shot. Moss, McDowell, and Stewart were arrested and brought to jail to await trial, but an angry white mob broke the three men out and lynched them. Ida strongly denounced the racial murders in the paper and was transformed into an investigative reporter. With a loaded pistol packed, she spent two months scouring the South looking into more than 700 lynchings that had occurred in the previous decade. In her search, she uncovered the various ways black people had been murdered in the South: some drowned, some hanged, others mutilated or burned alive, and still others beaten to death or shot, all of them because their skin was a darker hue. Ida reviewed photos, interviewed eyewitnesses, and examined newspaper articles. When she needed to, she hired private investigators.

In this, Ida exemplified a great deal of courage at a time when women could not vote and were afforded few rights, and black women yet fewer. The information she gathered was poured into anti-lynching articles that figured in her broader campaign, but one editorial had gone too far in the eyes of local whites. A white mob forced its way into her newspaper office and destroyed her equipment while she was in New York. She was warned to never return south, thus began her activism in the North.

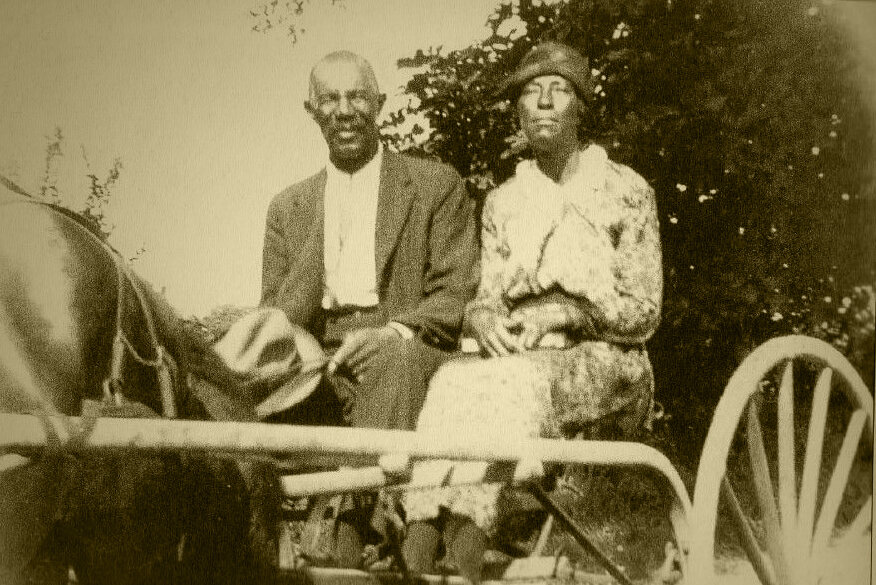

Ida continued her anti-lynching campaign in New York, writing a detailed lynching report for the New York Age, a paper run by former slave T. Thomas Fortune. But it wasn’t all activism and reporting for Ida. In 1895, she married Ferdinand Barnett and became Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Together the couple had four children. Ida established several civil rights organizations in her day, including the National Association of Colored Women along with her friend Mary Church Terrell, and civil rights luminary Harriet Tubman. And like Mary Church Terrell, Ida was counted among the co-founders of the NAACP. She fought tirelessly for women’s suffrage and lived to see the fruits of her labor (and that of many others) with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, allowing women the right to vote. Ida died on March 25, 1931, in Chicago, Illinois. The cause of death was kidney disease. She was 68 years old.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Mary Church Terrell was a black suffragist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century who also advocated for racial equality.