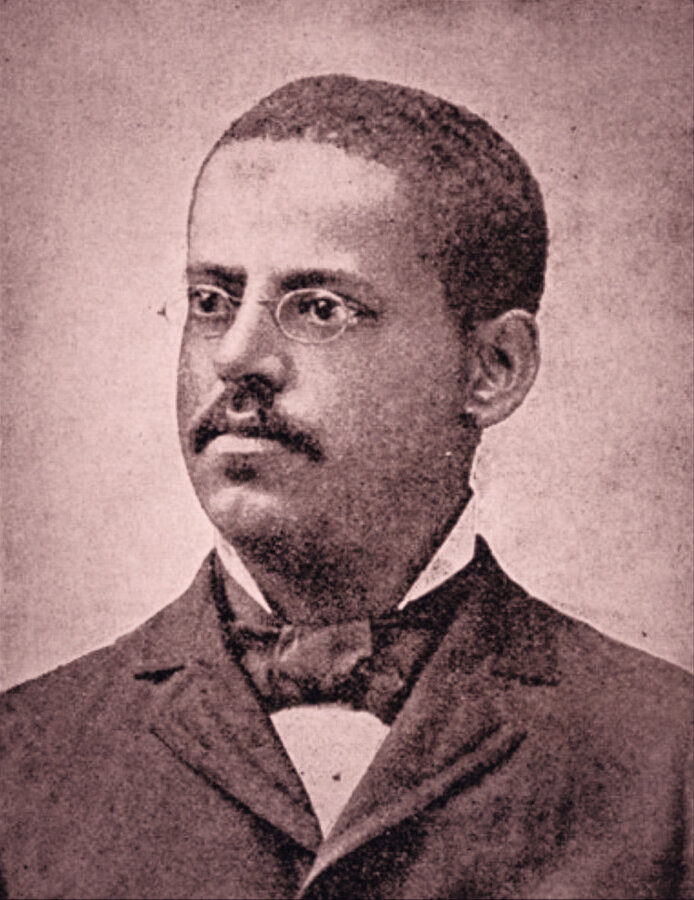

Horace King

The Respected Bridge Architect and Builder in the Deep South

Portrait of bridge builder Horace King. In the public domain.

At a time when a small percentage of slaves could read or write, one slave from the Deep South defied the odds by becoming a well-regarded bridge builder in the region. Horace King is noted for constructing impressive lattice truss bridges made of heavy timber between the 1830s and 1880s, which required precise knowledge of how trusses carried stress loads. His bridges spanned many important rivers in Georgia, northeast Mississippi, and Alabama. King started his bridge-building career as a slave, partnering with his master John Godwin. But by 1860, King was among the wealthy free blacks of Alabama who traveled without restriction. King became so respected and sought after by white Southerners that, over time, several towns falsely credited him as the architect of bridges and buildings he likely did not build.

Horace King was born a slave in Chesterfield District, South Carolina on September 8, 1807. He was of mixed African, European, and Catawba heritage. Upon his master’s death, he was purchased by contractor John Godwin of Cheraw, South Carolina in 1830. King learned to read and write at an early age, and he acquired carpentry and mechanics skills as a teen. He remained near his place of birth until the age of 23 and was introduced to bridge construction around age 17.

In 1824, a bridge architect named Ithiel Town traveled to Cheraw, South Carolina to aid construction efforts on a bridge project at the Pee Dee River—Godwin had been contracted to work on the same bridge. Four years later, the span was replaced. While records do not indicate whether or not King worked on the bridge, Ithiel Town’s signature lattice trusses figured prominently in Horace King’s bridge architecture going forward, so he had taken special note.

Photo of a bridge crossing the Chattahoochee River in Eufaula, Alabama. It was designed by Horace King in 1839. Courtesy of Alabama Writers’ Project/Wikimedia Commons.

In 1837, John Godwin, perhaps in an attempt to protect his valuable investment from the hands of creditors, transferred ownership of Horace King to his wife Ann Godwin and her uncle William Carney Wright of Montgomery, who was also her financial guardian. Ann and William allowed King to marry a free black woman named Frances Gould Thomas in 1839. This was unusual for a slave master, but King was no ordinary slave. Since Frances was free, this guaranteed the freedom of children produced from her union with King, of which there were five.

In the years that followed his marriage to Frances, King continued to construct bridges in partnership with his former master, John Godwin. Godwin negotiated the proposed fees with investors, while King oversaw design and construction. While the investors made their money by collecting bridge tolls, revenue derived from the building projects was likely split between Godwin and King, and by 1946, King was able to purchase his freedom. His working relationship with Godwin, however, remained the same until Godwin died in 1859.

Four years earlier, King established a different partnership with two men for the Moore's Bridge project, which was constructed over the Chattahoochee River. Instead of taking his usual fee, King opted for stock this time and essentially owned a thirty-three percent stake in the bridge. King moved his family to Moore’s Bridge around 1858, and following his master’s death, he was able to travel quite freely throughout the South via railroad to oversee various construction projects. As a show of respect, King erected a monument over his master’s grave.

Frances and the children collected tolls on Moore’s Bridge and farmed the land there. The tolls served as steady income for the family while King continued to design and build bridges and buildings in Georgia and Alabama. This dynamic lasted until July 1864, three years into the Civil War. That month, a Union cavalry commanded by General George Stoneman rode in and burned Moore’s Bridge down. Frances died a few months later and King married another woman, Sarah Jane McManus, the next summer.

Floating spiral staircase in the Alabama capitol designed by Horace King. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Union army burned many of King’s bridges during the Civil War, and while his sympathies were not with the South, he was contracted to build various projects for the Confederacy. They also forced him to block certain waterways in Georgia and Alabama to prevent Union forces from entering. The end of the war provided many opportunities for builders, and King benefitted from a bevy of projects assigned to him, such as a 32,000-square-foot cotton warehouse in Columbus, reconstruction of the Columbus City Bridge, three other bridges, two factories, an Alabama courthouse, and several other items.

At the dawn of the Reconstruction era, King ran for public office and was elected as a state legislator in Alabama. He successfully ran for re-election once and then withdrew from public life. He moved his family to LaGrange, Georgia shortly after and redoubled his bridge-building efforts. His construction interests expanded to include businesses and schools. In the 1870s, King began handing over construction oversight to his five children, and they established the King Brothers Bridge Company.

Horace King’s health deteriorated in the 1880s, and on May 28, 1885, while in LaGrange, he died at the age of 77. King has since received various posthumous honors, and he is fondly remembered throughout the South and beyond for his creative contributions.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Norma Merrick Sklarek was a pioneering female architect who accomplished several important firsts in her field and was a prominent leader in architecture up into her retirement.