Norma Merrick Sklarek

The First Licensed Black Female Architect

Norma Merrick Sklarek pictured in front of Commons-Courthouse Center, located in Columbus, Indiana. This is one of the buildings she designed in 1973 while at Gruen Associates.

Norma Merrick Sklarek’s name was added to the annals of history when she became the first licensed black female architect in New York and California. In 1980, she was also the first black woman to be awarded a fellowship by the American Institute of Architects. Half a decade later, she made history again as a founder of the architectural firm Siegel, Sklarek, and Diamond, which was a partnership with Margot Siegal and Katherine Diamond. No other black woman before her had established and managed such a firm.

Norma Merrick Sklarek was born in Harlem, New York on April 15, 1926. Her parents were Dr. Walter Ernest Merrick and Amelia Willoughby, who worked as a seamstress. Walter and Amelia moved to Harlem from Trinidad, but after Norma was born they later settled in Brooklyn. Norma studied architecture at Columbia University and earned her historic degree in 1950. Aside from being the only black female architect in America, women on a whole made up a slim minority in the field. Only one white woman was in her graduating class.

After graduating, Norma was hired as a junior draughtswoman at the New York Department of Public Works, where she remained until 1954. While there, she applied to nineteen firms but was rejected by all of them. That year, her bosses pushed her to take the architecture exam. In doing so, Norma succeeded in becoming the first black female architect licensed in New York. When she applied to the next firm, Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill the next year, she was hired. She worked at Skidmore until 1960.

Norma became a single mother during this time, and her mother helped raise her two children while she worked during the day and taught evening classes in architecture at New York City Community College. After leaving Skidmore in 1960, Norma relocated to Los Angeles, California to work for Gruen Associates, where she experienced an upswing in her career. Two years after joining the new firm, she became a licensed architect in California, while retaining her license to practice architecture in New York. In 1975, Norma wrote to the vice-chancellor at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), where she served on the faculty:

“As far as I know, I am the first and only black woman architect licensed in California. I am not proud to be a unique statistic, but embarrassed by our system which has caused my dubious distinction.”

Norma was so adept in her field that by 1966, she was named director at Gruen, another first for a black American female. But her rise to prominence was met with its share of obstacles. In the male-dominated field of architecture, women were rarely acknowledged for their creative contributions. A black woman, albeit a director, had less of a chance of being recognized for their work. This was the case with Norma. Despite her collaboration on high-profile projects that included California Mart, San Bernardino City Hall, Columbus, Indiana’s Commons Courthouse Center, and the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, Japan between 1963 and 1976, design credit went to an architect from Argentina named César Pelli. Norma was seen as the project manager rather than the designer.

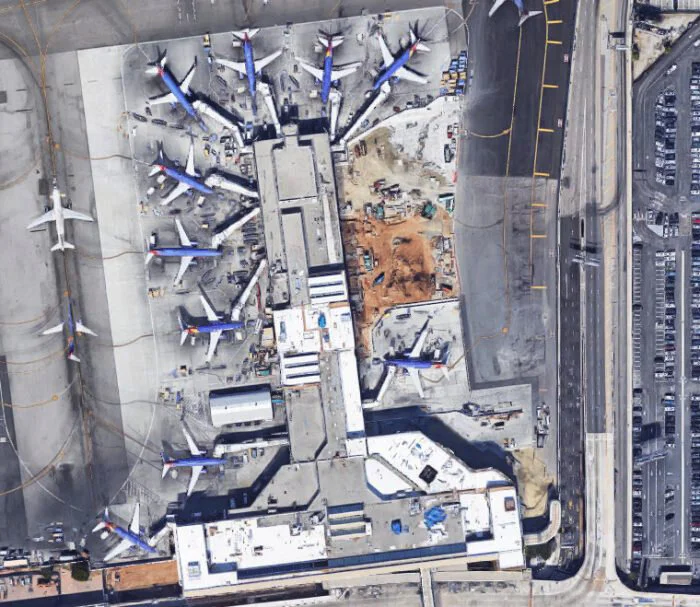

While at Welton Becket Associates, Norma Sklarek was named project director of the Terminal One construction project at the Los Angeles International Airport in 1984. Photo courtesy of Google.

Despite the disregard for her creative efforts, Norma remained at Gruen Associates until 1980. That was the year she also became the first black female fellow of the American Institute of Architects. Norma then accepted a position at Welton Becket Associates, a firm that appointed her as project director for a construction project at Los Angeles International Airport. A new station at Terminal One was being built, which would cost $50 million and had to meet a completion date that landed in the first quarter of 1984 before the summer Olympics commenced. Norma would later say that, while many projects were underway as she was overseeing her own, male architects regarded her with skepticism because she was a black female. But construction of Terminal One was the only project at Los Angeles International Airport that finished on schedule before summer.

Norma left Welton Becket Associates the year after her big project and co-founded Siegel, Sklarek, and Diamond, an all-female firm (one black, two white) that at the time was considered the largest such architecture firm in the U.S. Norma saw this move as the surest way to remove some of the obstacles present in her field and allow her to showcase her design skills, build a proper portfolio, and establish an impressive work history while receiving due credit.

Norma Merrick Sklarek (at center) poses with business partners Margot Siegel (left) and Katherine Diamond (right). The three women founded Siegel, Sklarek, and Diamond in 1985, considered the largest all-women architectural firms in the U.S. at the time. Photo courtesy of the Los Angeles Times.

Norma joined another Los Angeles partnership in 1989 called JERDE, which, according to them, is:

“a diverse group of designers, architects, and thinkers who put people and experiences first.”

Norma later taught at UCLA and became director of the University of Southern California Architects Guild. While she retired in 1992, she did not do so quietly. Norma was appointed to the California Architects Board by the governor and was chair of the National Ethics Council that was part of the American Institute of Architects. While at home in Pacific Palisades, California, Norma died of heart failure on February 6, 2012, at the age of 85.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Lewis Howard Latimer was a black inventor and engineer who contributed to the patenting and improvement of the incandescent light bulb and the telephone.