Juneteenth

The Official Emancipation Day for Black Americans

The word Juneteenth is a portmanteau, a word that blends the sounds and combines the meanings of two others, in this case, “June” and “nineteenth.” It is derived from a general order announcing the emancipation of slaves that was issued on June 19, 1865, by Union Army general, Gordon Granger. The Civil War had ended just two months earlier, and the general order came two and a half years after President Abraham Lincoln’s original Emancipation Proclamation, which read:

“all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State [...] shall be then, thenceforward and forever free….”

Yet when General Granger and eighteen hundred troops of the 13th Army Corps arrived in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865, they realized blacks were still being held as slaves. Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered in Virginia, and Texas, which had seceded from the Union on February 1, 1861, formally fell. This was the reason for General Granger’s visit: to assume authority over the people of Texas and enforce Lincoln’s original proclamation, which was issued January 1, 1863. While the Emancipation Proclamation had seen close to 200,000 blacks enlist in the Union Army to fight the South, 250,000 slaves remained in Texas following the war, many unaware of Granger’s general order.

General Order No. 3 was handwritten and read by General Granger as he stood on the balcony of Ashton Villa, former headquarters for the Confederate Army. This officially ended slavery in the state of Texas. The order reads as follows:

Head Quarters, District of Texas

Galveston, Texas, June 19, 1865

General Orders, No. 3

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

By order of Major General Granger

F.W. Emery

Major A.A. Genl.

The “proclamation from the Executive of the United States” refers to Abraham Lincoln, who was dead, yet his order lived on. Texas was home to the last remaining legally enslaved blacks in the U.S. While a messenger had been sent to Texas to issue the order by announcing the emancipation of blacks, many slave owners likely never heard the report, and if any did, business continued as usual with a free labor force. Since Texas remained a Confederate state until General Lee’s surrender in April 1865, emancipation was not enforced. General Granger was given command of the District of Texas and dispatched to Galveston with Union troops for this reason.

After General Granger read the order publicly from the balcony of Ashton Villa, he sent his men marching through Galveston to read the general order in various locations. These included their headquarters at the Osterman Building, the local courthouse, and the Negro Church on Broadway (now known as Reedy Chapel-AME Church). All Texans were officially informed that, per Lincoln’s original proclamation, all slaves were now free.

The annual celebration of Juneteenth arose from this event. Officially called Emancipation Day, June 19th is also called Freedom Day and Juneteenth Independence Day in some circles. It would seem that the arrival of General Granger and his Union troops—coupled with their grand announcement—instantly led to 250,000 slaves experiencing freedom, but this couldn’t be farther from the truth. Some chroniclers of Juneteenth’s history would have us believe otherwise. One source, National Today, a site that tracks holidays and special moments on the cultural calendar, writes:

“Granger’s arrival with the grand news stirred the air with jubilance and massive celebrations across the state. A former slave named Felix Haywood gave his recount of the first celebration in 1865 [...]—‘We was all walkin’ on golden clouds […] Everybody went wild […] We was free. Just like that, we was free.’ ”¹

Felix Haywood, an elderly blind ex-slave from San Antonio, Texas may have spoken this account, but what happened immediately following the proclamation of the order in Galveston was quite different for many. The news spread quickly on the relatively small island city of Galveston, but the day of freedom did not come as expected. In the book, Lone Star Pasts: Memory and History in Texas, Elizabeth Hayes Turner, a professor of history at the University of North Texas, writes:

“The former Confederate mayor rounded up black ‘runaways’ and held them for return to their owners. The Union Army’s provost marshall went along with this action but did so for the purpose of holding them as laborers for the military. Freedmen who entered the town after that found themselves pressed into military service. Although the announcement had come, for many, freedom still seemed elusive.”

Freedom did come to Galveston when Union troops occupied the island, but even with eighteen hundred troops, Granger’s general order took some time to reach the ears of plantation owners and their 250,000 slaves across the vast stretches of Texas. Some government agents did not arrive at distant plantations for months, and after they did arrive, plantation owners decided when and how to relate the news to their slaves. Many waited till after the season’s harvest to do so. Turning to Elizabeth Hayes Turner once more, concerning Texas slaves, she writes in Lone Star Pasts:

“When they did get the news and attempted to act on it by leaving, their immediate joy succumbed to despair as white vigilantes punished former slaves for preferring freedom to labor exploitation. Uncertainty mixed with high expectations for the future. The size of the state, the long distances between farms, the thin lines of Union protection, the remoteness from urban areas and from the heart of the defeated Confederacy conspired to bring emancipation more slowly into the interior of Texas.”

Historians estimate that thirty-eight thousand former soldiers from the Confederacy’s Trans-Mississippi Department headed home following the war, but they ransacked and pillaged towns as they went. Soldiers from the Texas division of this Confederate department did no less. Arriving at the state’s capital, Austin, battle-hardened ex-Confederate soldiers robbed the state treasury. Anarchy unfolded elsewhere in the state as well, and General Granger’s eighteen hundred troops were not enough to maintain order in all of Texas, nor provide adequate protection to so many scattered former slaves. The Freedmen’s Bureau sent reinforcements—Texas being the last state in the Union they assisted in this way—but its officers reached the state in early September 1865, nearly three months after June 19th.

Freedom celebrations were seen here and there among slaves following the public reading of General Order No. 3, but the idealized notion of widespread jubilation experienced by slaves immediately thereafter is a fallacy. Collected in Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves,² a former Rusk County slave from the era named Susan Merritt reported:

“Lots of niggers was killed after freedom … they owners have ’em bushwhacked ... shot down. You could see lots of niggers hangin’ to trees in Sabine bottom right after freedom, ’cause they catch ’em swimmin’ ’cross Sabine River and shoot ’em. They ’sho goin’ be lots of souls cry against ’em in Judgment!”

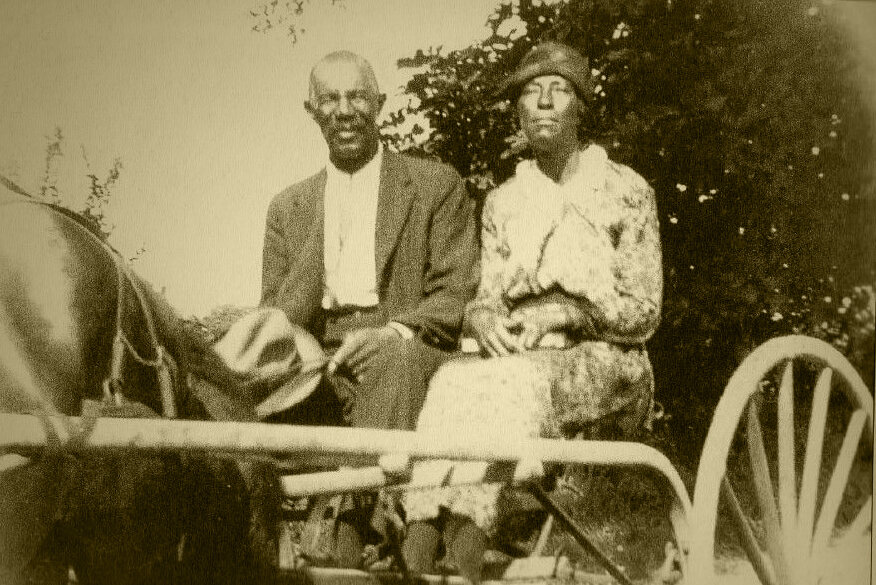

None of this was cause for celebration, which is probably why you see black people staring stone-faced at the camera in early photos depicting observances of Juneteenth. Irrespective of that, resilient ex-slaves persevered in the face of seemingly insurmountable adversity and turned June 19th into an annual day of remembrance, and eventually true celebration. The first official Juneteenth was observed one year after Union troops arrived in Galveston. June 19, 1866, was a day that saw blacks holding prayer meetings and singing spirituals, many wearing brand new clothes as a mark of newfound freedom. In time, black people in other states followed suit, embracing Juneteenth as Texan ex-slaves migrated throughout the U.S., taking the celebration wherever they went.

Unlike other proposed dates that have failed to hold in the minds and hearts of blacks—including Lincoln’s January 1, 1863, Emancipation Proclamation—June 19th endures. On the one hand, the January 1st date is overshadowed by New Year’s Day, and on another, many were still slaves in states where Union forces had not arrived to liberate them. Though individual states did not officially embrace the celebration or acknowledge the day for over a century, that began to change when the state where Juneteenth was born—Texas—declared it an official paid state holiday in 1980. During the regular session of the 66th Legislature, Texas House Bill 1016 passed, making June 19th “Emancipation Day” for blacks in Texas. Since then, Texans have celebrated Juneteenth with picnics, dancing, and parades. The Federal government, almost all individual states, and even private corporations have embraced the date as well, which stands as the oldest known official celebration commemorating the end of chattel slavery in the United States.

Update:

On Thursday, June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden signed a Congressional bill making Juneteenth a federal holiday. The event marked the 156th anniversary of the first Juneteenth. The United States has not had a new federal holiday since Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 1983.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

A brief history of Black History Month, the annual celebration of black achievement, and recognition of the central role black people have played in shaping U.S. culture and history.