Marian Anderson

The Acclaimed Singer Who Tore Down Racial Barriers

Marian Anderson was blessed with one of the most extraordinary voices a man or woman could possess. It allowed her to sing in the presence of presidents and kings, and thrill audiences around the world. Yet, her voice alone was not enough to win over certain racist individuals. Marian was black, and some people, like members of the Daughters of the American Revolution — or DAR — took no notice of her voice due to the color of her skin. In 1939, they refused to let Marian sing at the DAR Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. because they operated by a strict “white performers only” policy at the time. That’s when the First Lady, Eleanor, and her husband, President Roosevelt, stepped in. With their aid, Marian was able to give a grand performance in the open air on April 9th of that year. It took place in the nation’s capital, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, before an audience of 75,000 spectators, while millions more listened over the radio. On that memorable Sunday, Marian Anderson made history.

Marian Anderson was born on February 27, 1897, on Webster Street in South Philadelphia. The city itself was an enduring symbol of American independence, with the cracked Liberty Bell and Independence Hall residing less than a mile from her place of birth. Yet, as multiethnic as her city was, not all Philadelphians enjoyed the sense of freedom and liberty promised in the Constitution.

All four of Marian’s grandparents were ex-slaves, and she was born in the post-Reconstruction era, when America was still coming to grips with millions of blacks being integrated into society thirty-five years after the emancipation process was initiated. In his book The Sound of Freedom, historian Raymond Arsenault informs us that Marian’s father was John Berkley Anderson:

“… a devout Baptist who ‘neither drank, smoked nor chewed.’ ”

Her mother was Anna Delilah Rucker, a former schoolteacher who became a child caregiver to support her family. Though Anna had briefly attended the Virginia Seminary and College in Lynchburg without earning a degree, this allowed her to teach in Virginia, but Philadelphia restricted blacks — and only blacks — from teaching in the city without full credentials, according to the biography Marian Anderson: A Singer’s Journey by author Allan Keiler.

“Marian Anderson and her two younger sisters, Alyse and Ethel, all became singers, but even from a young age, it was clear that Marian’s voice was special.”

Unlike the rest of the family, Anna did not attend her husband’s Baptist church. She was a lifelong Methodist. Marian Anderson and her two younger sisters, Alyse and Ethel, all became singers, but even from a young age, it was clear that Marian’s voice was special. Marian’s aunt, Mary Pritchard (who was her father’s sister) was another musical member of the family. Mary was moved by her niece’s voice and encouraged her to join the junior choir of the Union Baptist Church at the tender age of six. Before long, Marian was performing sensational solos and occasional duets with her aunt, Mary. And she seemed to be able to hit any note as her voice filled the church building.

In time, Marian was tapped to sing at various local functions, for which she was paid a quarter of a dollar or more. But tragedy struck when she was twelve years old. Marian’s father, John, was a coal and ice dealer who plied his trade at Philadelphia’s Reading Terminal. One day at work, John suffered a severe head injury, and within a few weeks died at the age of 34. When he was alive, the family could not afford to pay for Marian’s formal singing lessons. Things grew exponentially worse following his death. Her mother, Anna, worked even harder to support her children. She did laundry and worked as a housekeeper at a department store scrubbing floors to make ends meet. Anna and her three daughters also moved in with John’s parents, yet Marian’s singing was not forgotten. Marian felt a sense of responsibility at so young an age and increased her performances, at times singing at three separate events in a single evening.

By this time her pay had increased to five dollars per performance, and with each payment, she saw that her mother received two dollars and each of her sisters one dollar. The final dollar she kept for herself. Because the family could not afford to purchase the necessary books and clothes for Marian to attend high school, she got a late start; so late that she ended up graduating at age 24 with the class of 1921. Marian continued to sing, and her performances started to take her farther afield, since more people thronged to hear her.

During her high school years, she even traveled by train to various cities to perform, her main venues being black colleges and churches. This of course meant that she was away from home and family for days at a time. But Marian desired formal training in order to take her singing to higher levels. She couldn’t afford a teacher on her own, but with the backing of several Union Baptist church members, who promised to pay her tuition, Marian walked to a music academy on Spruce Street intent on filling out an application. Her visit to the music academy resulted in a bitter racial lesson. She was ignored while a long line of whites was attended by a white female desk clerk. When the line emptied, Marian was told bluntly, “We don’t take colored.” In 1960, Marian later told a Ladies’ Home Journal reporter that the experience was a “painful realization of what it meant to be a Negro.”

“Marian was told bluntly, ‘We don’t take colored.’”

Marian recalled looking at the young girl in shock following her cold, hurtful words. She didn’t say a word in reply. She simply walked out of the building and tried to put music school out of her mind for a time. Years passed before she steeled her will and risked facing that kind of rejection again. It happened after World War I, when returning black veterans — after suffering the horrors of war in Europe — could not find work in their own country and were despised by whites at every turn. Those black soldiers went off to war and risked death for their racist countrymen; they returned to life in America where they were refused to be considered full citizens. If they could endure such treatment, then she had little recourse but to show her own resolve.

It was while attending the South Philadelphia High School for Girls that her principal, Dr. Lucy Wilson, made it possible for her to perform in school and thereafter audition for a potential voice teacher, the demanding Giuseppe Boghetti,¹ for whom race meant nothing. Their first meeting, which took place in early 1920, was attended by Dr. Wilson and a close friend named Lisa Roma. During that meeting, Boghetti, who, in Anderson’s own words was “severe, even gruff,” expressed to her that he was short on time and did not want to take on new students. In fact, he was only there as a personal favor to Miss Roma. Dr. Wilson looked unhappy to hear this. Nonetheless, the audition went forward.

Marian recalls averting her eyes from Boghetti while she sang an old spiritual called “Deep River.” At the end of her song, Boghetti, in a complete about-face, said, “I will make room for you right away.” According to Raymond Arsenault’s biography of Marian, Boghetti then claimed he only needed two years to fully train her, adding:

“After that, you will be able to go anywhere and sing for anybody.”

The lessons didn’t begin right away, however. Money needed to be raised to cover the tuition. To that end, the Union Baptist Church sponsored a benefit concert headlined by Marian, which the surrounding community fully supported via a sizeable turnout. The concert raised just shy of six hundred dollars, enough to cover one year of singing lessons. Her early training included learning the techniques of bel canto singing, a classic operatic style that got its start in Italy in the late sixteenth century — and which is supposedly the quintessential way to sing operas.² Marian was also coached in Italian and tutored in French. And while she was considered a contralto, Marian could reach the full-voiced high notes of a soprano or the low register of a baritone.

With Boghetti’s training, Marian transitioned from singing merely black church music, which restricted her to performing at a limited number of venues, to singing standard concert repertoire of the day. Just prior to her high school graduation, Marian made her first appearance — though a minor one — at Carnegie Hall in New York, during an annual concert of the Martin-Smith Music School. Marian was hired as an assistant but was allowed to perform. Her second Carnegie Hall performance — another minor one — came the next winter, during a farewell concert for Sidney Woodward, one of the most celebrated black tenors at the time. This merely whetted her appetite for more, but her real breakthrough would come in the next decade.

In the early 1920s, Marian toured the United States with a popular black accompanist named Billy King, a Philadelphia native. When they traveled by train, they were forced to ride in a car designated for blacks, which was the worst one. Although, by law, railway companies were supposed to provide equal accommodations for both whites and blacks.³ Touring the Jim Crow South proved a more bitter ordeal. Blacks were not allowed in hotels, unless they were servants, so Marian and King had to lodge in private homes. After enduring these and other racial prejudices, such as concert opportunities being closed to her, Marian moved to Europe. She received scholarships that allowed her to study abroad. In Germany, she learned songs from the romantic period known as German lieder. To that she added Italian arias, Russian songs, and Finnish folk songs. At the height of Marian’s career, her repertoire included more than two hundred songs in nine languages. While her concerts included classical songs, or lieder, by famous European composers, Marian usually included a selection of traditional black spirituals in each performance.

She experienced great success in Europe, beginning with her Berlin debut in 1930. Two Scandinavian tours would follow within three years, during which she sang for the kings of Sweden and Denmark. She gave successful concerts in Paris and London, and another tour took her to Spain, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Russia, and Austria. Following her sensational performance in Austria, noted conductor Arturo Toscanini — who was in attendance — is reported to have said that Marian possessed:

“… a voice heard but once in a century.”

Marian’s European tour was so successful, she caught the eye of an American impresario named Sol Hurok while in Paris. Hurok signed Marian to do a 15-concert tour in the United States.⁴ In 1935, Marian opened her American tour at New York’s Town Hall to great success, with the New York Times hailing her as:

“… one of the great singers of our time.”

In the very year the DAR refused to allow her to sing at Constitution Hall, Marian was invited to the White House to sing for England’s King George and Queen Elizabeth. Though she received several awards throughout her distinguished career, racism and discrimination remained significant features of Marian’s life, but she persevered with dignity and strength. Doors continued to open for her, including the doors of Constitution Hall, whose forbidden stage she was finally allowed to grace with her presence and voice in 1943 for a war-benefit concert. Marian made history again on January 7, 1955 when she became the first black person to sing for New York’s Metropolitan Opera since it began in 1883. She was signed to her role by Rudolf Bing, manager of the Met, and her very presence in the company opened doors for other black opera singers.

Less than a decade before her own farewell concert, and the end of her singing career, Marian — already an American icon at the time — gave us an inspirational outlook in 1956. In reflecting on the country that refused to love her until she reached the pinnacle of success, Marian Anderson wrote in her autobiography:

“There is hope for America. Our country and people have every reason to be generous and good…. All the changes may not come in my time; they may even be left for another world. But I have seen enough changes to believe that they will occur in this one.”⁵

You may also be interested in:

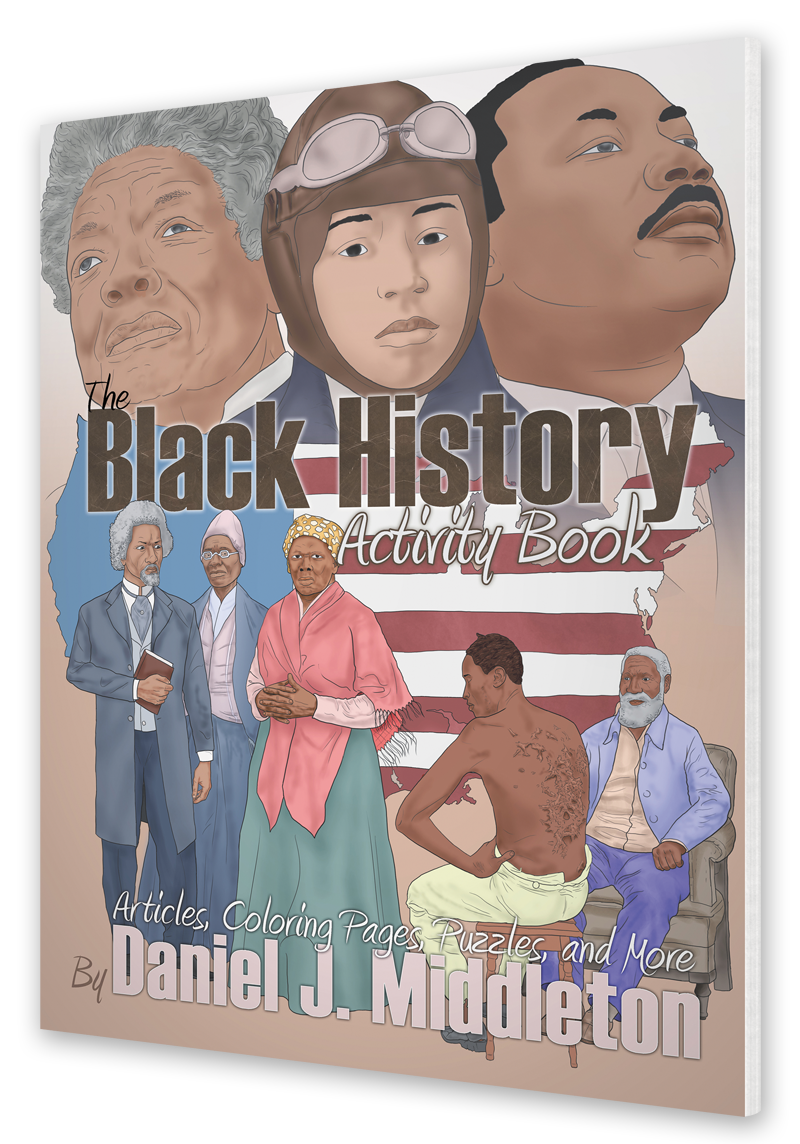

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Widely considered the pioneer of rhythm tap, a familiar and celebrated style in tap dancing, John W. Bubbles paved the way for generations of dancers to come.