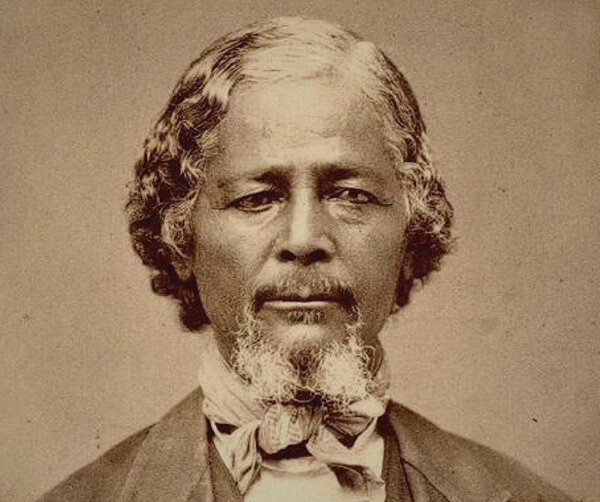

Matthew Henson

The Black Co-Discoverer of the North Pole

In his 1912 memoir, Matthew Henson, an early black explorer, claimed to be the first person to reach the North Pole. At the time, he was not even considered as a possible contender for that prize, largely because of his skin color. White explorers Robert E. Peary and Frederick A. Cook were the two prominent claimants in 1909, and newspapers ran splashy alternate frontpage exclusives announcing the success of both men. For 300 years, people from various nations had died attempting to reach the North Pole before Peary and Cook’s contest, but when all was said and done, the evidence to support the claim of either man was lacking. And in recent years, support for Matthew Henson’s claim has grown.

In a team of six explorers were Peary, Henson, and four Greenlandic Inuit locals known as Inughuit, who are the northernmost group of Inuit in the world. Even among them, Matthew Henson stood out. Aside from being a black explorer, which was rare in those days, Henson was also fluent in the Inughuit language, Inuktun. This allowed him to initiate trading with them and enlist their aid in navigating the region. Henson was also adept at building igloos, making sleds, hunting, and training dog sled crews. He was considered by Westerners as a better dog-driver than any other man alive, except the best among the “Eskimos” themselves, as the Inughuit were once called. Possessing the knowledge needed to survive in subzero temperatures in the arctic made Henson a key component of Peary’s expedition team. Peary even said of his indispensable black valet:

“I can’t get along without Henson.”

Yet, because he was a black man, Henson’s accomplishment went unrecognized by the world for decades. Matthew Alexander Henson was born in Charles County, Maryland on August 8, 1866, to two freeborn sharecroppers. His family moved to Washington, D.C. when he was very young, and his mother died when he was seven years old. He was orphaned when his father died not long after, forcing him and his siblings to live with their uncle. He attended the N Street School in Washington, D.C. for a few years, and after leaving school at age 12, he walked to Maryland and found work as a dishwasher at a restaurant. That did not last long, however, because after listening to adventurous sea tales spun by the various sailors who frequented the restaurant, Henson was off again in search of a ship. In Baltimore, he talked his way into a job as a cabin boy aboard the SS Katie Hines, a merchant ship commanded by Captain Childs. The ship set sail for China, and Henson later wrote in his memoir, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole:

“After my first voyage I became an able-bodied seaman, and for four years followed the sea in that capacity, sailing to China, Japan, Manilla, North Africa, Spain, France, and through the Black Sea to Southern Russia.”

It was Captain Childs who took the young Henson under his wing and provided necessary seamanship training. But Childs, through the use of the ship’s private library, also saw that Henson received other fundamental education as well, including history, geography, literature, mathematics, and carpentry. Henson’s time aboard ship lasted until about 1883, the year that Captain Childs is believed to have died. Over the next few years, Henson found odd jobs here and there on both land and sea in Providence, Rhode Island; Boston, Massachusetts; Buffalo, New York; and New York City. He eventually ended up back in Washington, D.C. where he secured work as a stock clerk in a clothing and hat store on Pennsylvania Avenue called B. H. Steinmetz and Sons. It was there, in 1887, that Henson met Lieutenant Robert E. Peary, a young officer in the U.S. Navy Corps of Civil Engineers, who was in search of a tropical hat. Their encounter ended with Peary deciding to hire Henson as a valet for an upcoming surveying expedition in Nicaragua.

Sam Steinmetz, an owner of the store, permitted Henson to accompany Peary and promised that his job would be there when he returned. Henson went on the expedition and assisted in laying the surveyor's chain—a distance measuring device—and helping with other small tasks. When he returned to Washington, D.C., his job was waiting for him, but Peary called him soon after and arranged for him to work as a clerk and messenger in his government office at the League Island Naval Yard in Philadelphia.

In April 1891, Henson married Eva Flint, but six years later, after suspecting infidelity on her part, he divorced her. Shortly after marrying Eva in 1891, Henson joined Peary for what was dubbed the North Greenland Expedition. On that trip, Henson embraced local Inughuit culture and learned to speak Inuktun. During that year, he added Arctic survival skills to his repertoire, which already included his ability to shoot, canoe, do woodwork, handle sled dogs, break trails, and survey. All of this made him an invaluable asset to Peary’s expeditions.

Another trip to Greenland was organized in 1893, and Peary planned to chart the entire ice cap this time around. That particular journey, which lasted two years, was near tragic. Peary's team nearly starved to death, and they only managed to survive by resorting to eating all but one of the precious sled dogs. Regardless of the harrowing experience, two more trips to Greenland followed shortly after. In fact, between June 1891 and August 1902, Peary, with Henson at his side, spent a total of seven years traversing the Arctic. They covered over 9,000 miles traveling predominantly by dogsled across northern Greenland and Ellesmere Island in Canada. Several of their trips were made in attempts to reach the North Pole, but with no success. A 1906 expedition was attempted as well, but a six-day blizzard and widening leads (or narrow, linear cracks) in the ice, forced Peary and his crew to turn back.

Henson saved Peary’s life at least twice during their expeditions. When Peary was attacked by an enraged musk ox, Henson was there to shoot it. And when frostbite and gangrene came to claim Peary in the Arctic, it was Henson who cared for him until he could receive proper medical attention. Yet Peary paid Henson very little for his many efforts and various skills. Henson earned between $25 and $35 per month for all the expeditions, except the final one, where he received at least $50 per month, in addition to an unconfirmed bonus. And that final trip was the one to end all others.

“Henson saved Peary’s life at least twice during their expeditions.”

Henson and Peary’s seventh and final trip together—and Peary’s final attempt to reach the North Pole—began on July 6, 1908. They sailed from New York City in a newly overhauled ship, the SS Roosevelt, which was stocked with supplies and filled with an able crew for the expedition ahead. Once they reached Greenland, they were joined by forty-one Inughuit men who brought more supplies, as well as 246 dogs.

The Roosevelt arrived at Cape Sheridan at the northern tip of Ellesmere Island on September 5th. Twenty-four men and their supplies were transferred north to Cape Columbia via dog sled to set up a base camp. Two men were to go ahead of the main group as a pioneer division and cut a trail that stretched from the base camp to the North Pole. A supply division was to follow, and they were to break trail, build igloos, and leave supplies along the route for the main party. But as the explorers progressed, food became scarce, and several men were sent back to Cape Columbia, while a few pressed on. When the group was 133 nautical miles away from the North Pole, the final support group was sent back as well. That left only Peary, his best man Henson, four Inuits, and 40 dogs.

Henson claimed to have arrived at the North Pole on April 6, 1909, 45 minutes before Peary did. Since he did not know how to use a sextant, he determined his position by dead reckoning. Henson’s ability to dead reckon was astounding, and Peary had tested him on it. On one trip, Henson had estimated a thousand-mile journey in his head and was only off by 20 miles.

Four Inughuit men had also reached the North Pole, and all of them stood there with Henson holding up flags in a photo that marked the occasion. Yet it was Peary who took the credit for being the first person to reach the North Pole. Upon their return to the states, a newspaper ran an article quoting Henson. He said he had been part of a leading group that overshot the pole by several miles:

“We went back then and I could see my footprints were the first at the spot.”

Aside from the newspaper article, Henson barely received any recognition for his involvement for several decades. While Peary retired in comfort and was praised for his efforts, Henson remained obscure and subsisted on meager pay, even though he was able to secure a government job in the U.S. Customs House in New York City. He retired at age 70 on a pension of around $1,000 a year, but that was not enough to sustain him. His second wife, Lucy Jane Ross, who worked at a bank, was the one who mainly provided for him until his death. Henson did eventually receive numerous awards and honorary degrees before departing this world, but only in recent years has he received the recognition he deserves. In 2000, Henson was posthumously awarded the Hubbard Medal, the highest honor of the National Geographic Society.

Matthew Henson died at age 88 in New York City on March 9, 1955. He was buried in the Bronx at the Woodlawn Cemetery in a funeral that was attended by more than 1,000 people. Decades later, in 1988, both the bodies of Henson and his wife were disinterred and reburied at Arlington National Cemetery, adjacent to Robert E. Peary’s grave.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Born a slave, Stephen Bishop was an early explorer who became the first guide at Mammoth Cave, and his discoveries brought him international recognition.