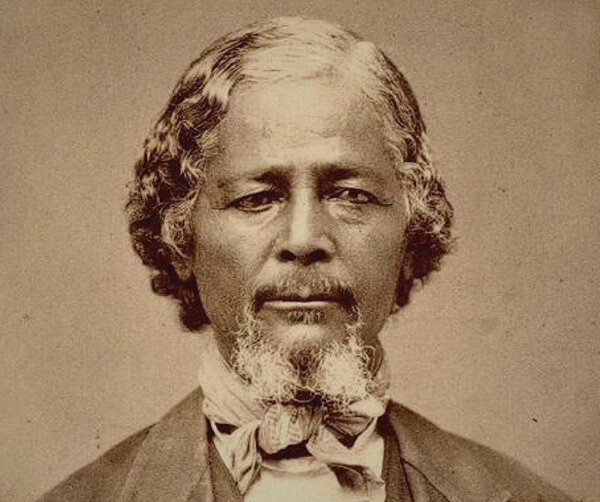

Stephen Bishop

The First Great American Cave Explorer

Stephen Bishop exploring Mammoth Cave.

Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave is considered more than just a cave to many. It includes deep river valleys, rolling hills, and diverse plant and animal life. All of this qualifies it as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and International Biosphere Reserve. But the cave itself—the longest known cave system in the world—is the feature that transformed Mammoth into a must-see destination that draws over two million visitors each year. One man is responsible for mapping the limestone labyrinth’s most popular spots and making them accessible to tourists: a mixed-race slave named Stephen Bishop.

Stephen was born into slavery in 1821, but very little is known of his early years. He was believed to be the biological son of Lowry Bishop, a white farmer who was his previous owner. In the spring of 1838, when Stephen was 17, his new owner, a lawyer named Franklin Gorin, brought him and two other slaves to a cave he had recently purchased for $5,000. Intending to turn the cave into a tourism site, Gorin’s slaves would serve as guides. The cave, which contained five levels stacked one on top of the other, featured underground rivers, interconnected caverns, pits, underwater springs, and passageways that stretched for 412 miles.

Archaeologists have discovered that early Native Americans explored the first three levels of the cave system perhaps as far back as 4,000 years ago. As white settlers made their way west following several expeditions, the cave was rediscovered in the 1790s. In another two decades, during the War of 1812, the cave was mined for potassium nitrate (or saltpeter) for use in gunpowder. Early tourism efforts began in 1816, and even in 1838, when Gorin took possession of the cave, only eight miles of the entire system had been explored.

The superintendent who once ran the mining operation took Stephen on a tour of some of those eight miles and he received instruction on the then-current methods of being a tour guide. Thus he began guiding tourists, but he also ventured off on his own to explore passages and areas that were yet unknown. Stephen is now regarded as one of the bravest spelunkers who ever existed because his explorations were extremely dangerous at the time.

“Stephen is now regarded as one of the bravest spelunkers who ever existed….”

The cave is much different than it was in Stephen’s day. Electricity flows through the cave system now, and sediment, debris, excess plant growth, and rubble have all been removed. Stephen had to contend with all of that. He navigated the cave with merely a rope and a lantern, which could have gone out at any moment, leaving him stranded in perfect darkness many miles within the cave’s complex. Despite the danger, Stephen managed to make several wonderful discoveries by opening up unseen sections of the cave to exploration and tourism. Yet, some of the cave’s branches he discovered beyond the hole of darkness known as bottomless pit were not found again until fairly recently, through the use of modern equipment and tools.

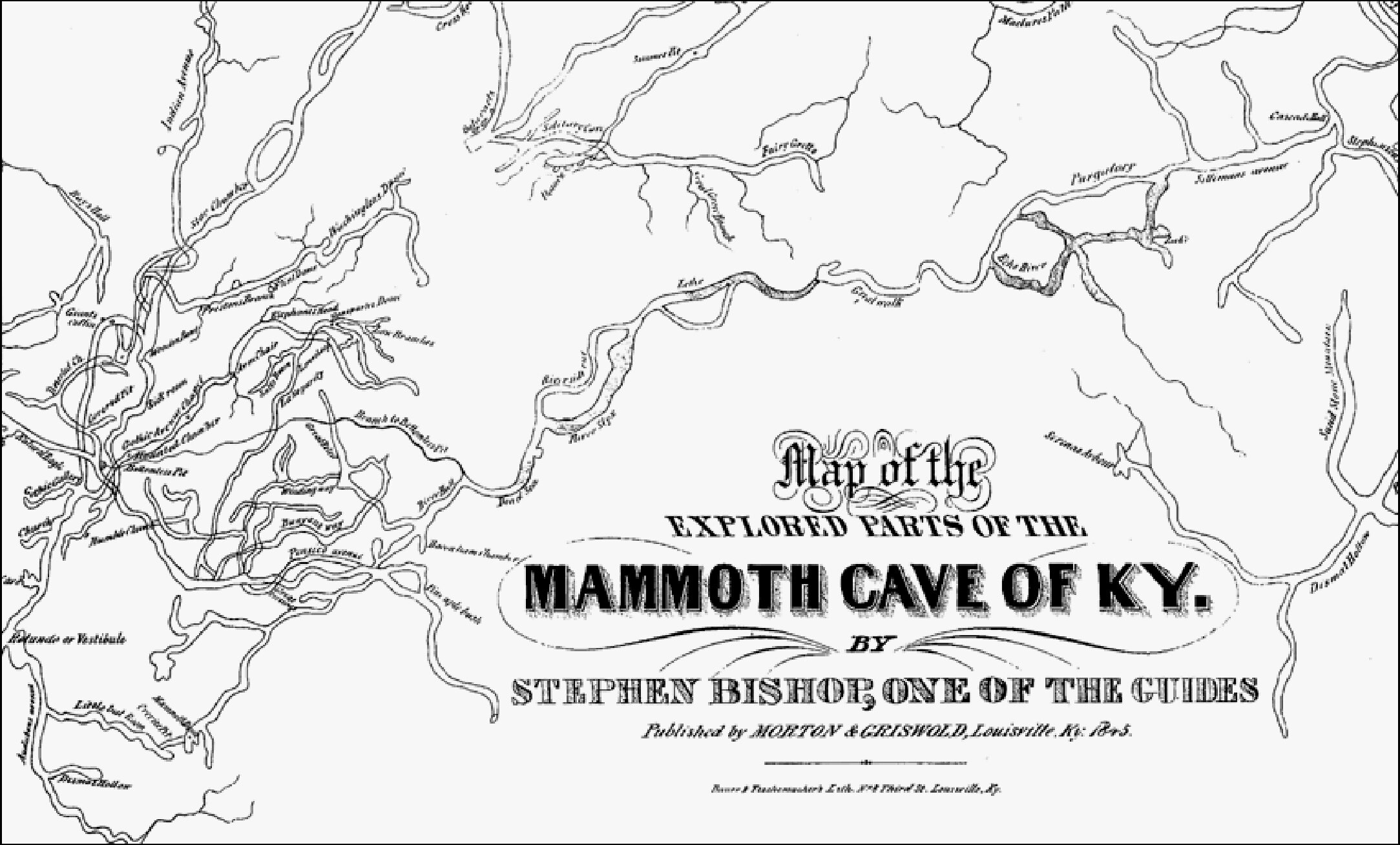

Stephen was sold to a new master the next year, in October of 1839, along with Mammoth Cave. The new slave owner was Dr. John Croghan, nephew of William Clark, co-leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. When Croghan discovered Stephen’s knowledge of the cave system, he invited Stephen to his Locust Grove estate for two weeks in 1842 and had him draw a map of the cave’s underground passages and rooms from memory. In a rare turn for that era, when the map was published two years later, Stephen received full credit. His map, which featured 10 miles of the cave (including the portions he discovered and explored) was in use for the next forty years. The map was as accurate as was possible for the time, absent the use of an instrumental survey, but he went to great lengths to represent the relative lengths and dimensions. He even indicated water using cross shading like modern cave cartographers do today.

Stephen named many of the areas of the cave he discovered, and those catchy names have endured: Fat Man’s Misery—the narrow, winding ancient riverbed—Echo Rivers, River Styx, and Great Relief Hall. Being self-educated (he even knew a little Latin and Greek) and possessing a knowledge of geology allowed Stephen to become intimately familiar with Mammoth Cave. That familiarity, together with his colorful personality, made him a great tour guide, and he was loved by the rich, white tourists whom he guided through miles of passages for hours. It was Stephen himself—about whom articles and books were written and circulated throughout the world—who attracted visitors to that rural estate to encounter both the brave man and the mysterious cave.

Stephen also trained his eventual successors, famed slaves Mat Bransford and Nick Bransford—no relation—who Gorin leased for $100 a year. The signatures of these two guides, made from candle smoke, can still be seen throughout the cave. The two Bransfords made discoveries of their own which they infused in their tours. As it happens, descendants of Mat Bransford took up the reins and became popular tour guides of Mammoth Cave as well.

While at Locust Grove, Stephen met and married Charlotte, another enslaved worker. She came to live with him near Mammoth Cave and worked at the hotel on the property. Stephen’s enslaver, Dr. John Croghan, died in 1849 from tuberculosis. Per his will, the 28 slaves he held were to be free seven years past the time of his death. Stephen and his wife were included in that list. They were emancipated in 1856, and a year later, the two sold 112 acres of land near Mammoth Cave they had acquired from their earnings. In another few months, Stephen’s cause of death is unknown.

Twenty years after Stephen was buried in an unmarked grave by his wife, a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania visitor promised to send her a new tombstone. A few years later, the stone was indeed purchased by that visitor, millionaire James Mellon. But the tombstone was once intended for a dead Union soldier. Mellon simply had the soldier’s name chiseled off and replaced with the inscription: “Stephen Bishop, First Guide & Explorer of the Mammoth Cave.” Stephen was only 37 years old when he died in 1857, yet Mellow listed his date of death as June 15, 1859. And while Stephen was never enlisted in the U.S. military, the symbol at the top of the tombstone depicting downward-pointing swords is usually engraved on war memorials to honor soldiers who fought and died in battle.¹

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Matthew Henson is the black explorer who is credited as the co-discoverer of the North Pole, along with Robert E. Peary.