Mound Bayou

The Historic Black Town in the Mississippi Delta

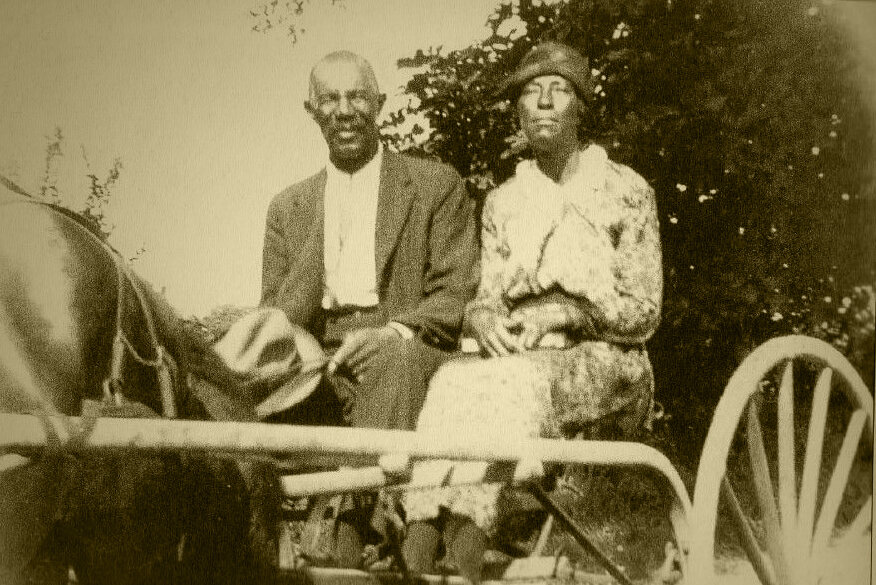

Early Mound Bayou settlers. Photo courtesy of Delta State University.

Mound Bayou, located in the central Mississippi Delta, was once a thriving haven for thousands of black Americans during Jim Crow. Former slaves founded Mound Bayou as an all-black town in 1887, and within it sprang up dozens of black-owned businesses, including two mills, three cotton gins, a train station, a library, a few schools, and even a bank. A town of this magnitude was unheard of at the time, and the economic development it enjoyed drew the attention of many, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who called Mound Bayou “The Jewel of the Delta.” Such high praise from a U.S. president was warranted, seeing Mound Bayou was a former wilderness swamp. At its height, Mound Bayou was the nation’s largest black town, and the most self-sufficient one in existence.

Three cousins founded Mound Bayou: Isaiah T. Montgomery, Joshua P. T. Montgomery, and Benjamin T. Green. They had been slaves on the same property in Warren County known as Davis Bend Plantation. Their former master was Joseph Davis, older brother of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate states. The cousins divided up the responsibilities required in establishing a town, with Isaiah Montgomery and Benjamin Green handling the business end of things, and Joshua Montgomery dealing with the legal aspect.

The first order of business was securing land, and Isaiah and Benjamin accomplished that with a down payment on 840 acres in the remote rural area of Bolivar County in July 1887. Isaiah had been hired as a land agent for the Louisville, New Orleans, and Texas Railroad, as its owners were planning to build a railway line through the Mississippi Delta, which required the establishment of towns. The rail company saw newly freed blacks as an untapped source of future revenue, particularly if they were able to establish some of those towns, hence why Isaiah and others like him were hired as land agents.

Benjamin T. Green and Isaiah T. Montgomery. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

After the land was purchased, Isaiah and Benjamin started to recruit settlers, from which they would draw a labor force. The land was densely overgrown with trees and undergrowth that was nearly impossible to navigate without cutting implements. Beyond that, wild animals still roamed the interior, and swamp fever eventually claimed the lives of a few settlers. More and more recruits descended on the swampland, the first waves comprising ex-slaves from Davis Bend Plantation, and then former slaves hailing from various parts of the South. Together, they did the grueling business of clearing the land. In 1907, Booker T. Washington published his account of Mound Bayou’s founding, saying:

“It was not the ordinary Negro farmer who was attracted to Mound Bayou colony. It was rather an earnest and ambitious class prepared to face the hardships of this sort of pioneer work.”

Under Isaiah’s leadership and planning, the forest and swamp were cleared, and settlers flocked to the black colony. The founders saw their positions improve as commissions from land sales poured in. Isaiah and Benjamin established the town’s single sawmill, from which everyone benefited. Then came a supply store, post office, cotton gin, school, and church. In 1898, Isaiah was appointed the town’s first mayor, and other settlers filled important posts, such as marshal, aldermen, and treasurer.

In 1942, the black fraternal organization the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor constructed a medical facility. It was the first hospital in Mound Bayou, offering forty-two beds. The hospital staff was a collection of graduates from Nashville’s Meharry Medical School, and they were all black. The town, therefore, seemed to lack nothing. NPR interviewed a Mound Bayou woman named Annyce Campbell who was born in the town in 1924. She says of the town:

“You name it, we had it! We had everything but a jail, to tell you the truth!”

While it is closed today, Taborian Hospital served black citizens throughout the Delta region after opening in 1942. Photo courtesy of Elissa Nadworny/NPR.

Annyce was born and raised when Mound Bayou enjoyed a period of prosperity. The tentacles of white supremacy were not long enough to reach into that particular black town, and Mound Bayou was even a haven from white oppression during the Civil Rights era. While blacks in other parts of the South were being dragged off and lynched, or beaten in broad daylight and attacked by police dogs, Mound Bayou residents could visit the various shops and black-owned businesses along their streets in peace. Students didn’t have to worry about segregation or receiving an inferior education. Sick residents could be treated at a local hospital where every physician, nurse, and orderly looked like them. Discrimination was nonexistent in Mound Bayou, and residents drank from any water fountain they wished.

But after reaching its apex, Mound Bayou’s prosperity began to decline in the latter half of the twentieth century. The town suffered economic downturns like any other community when markets spiraled. And antagonistic whites did encroach on the oasis from time to time. Internal political strife also wreaked havoc, but desegregation is what truly sealed the town’s fate. When blacks were finally allowed to integrate with whites, many left their native black towns for what they hoped were better prospects. By the 1960s, Mound Bayou was struggling. Today, the town exists as a husk of its former self, with few businesses remaining, the population largely reduced, and half of the children living below the poverty line. Its residents are now fighting to regain a semblance of the glory the town enjoyed during its heyday.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

South-View Cemetery, home to more than 80,000 black Americans who are buried on its grounds, is the first and therefore the oldest black stockholder corporation in the U.S.