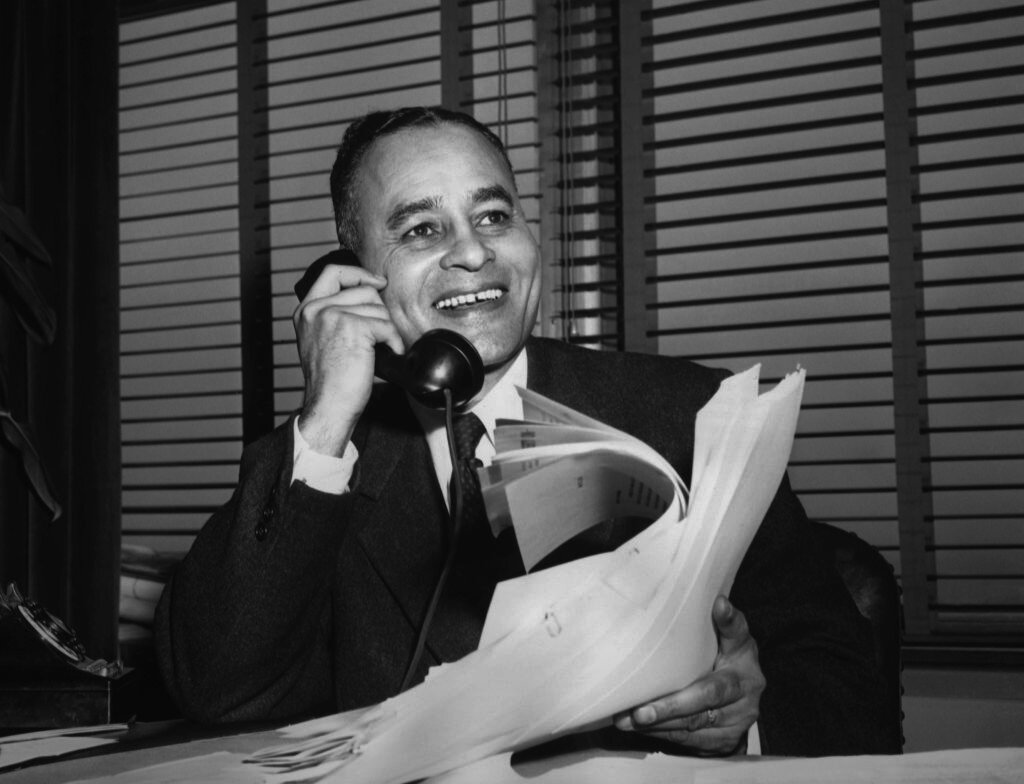

Ralph Bunche

The First Black Nobel Laureate

Among his many roles, Ralph Bunche was an international statesman, a scholar, a civil rights activist, and a tenured political science professor at Howard University. While relatively unknown to the public today, Bunche was a complicated figure who was instrumental in shaping international relations from the 1940s to the 1960s. During World War II, he was named chief of the Africa section of the Office of Strategic Services—the predecessor of the CIA. In the final years of the war, he was an adviser to the State Department and military, given his knowledge of Africa and its colonial areas of strategic importance—knowledge derived from academic study and actual fieldwork on the continent.¹ He also sat on a State Department subcommittee that established the United Nations, of which he was subsequently named Under Secretary for Special Political Affairs.

Ralph Johnson Bunche was born in Detroit, Michigan on August 7, 1903,² into a poverty-stricken family. His father Fred Bunche worked at a barbershop that was for whites only, while his mother, Olive (Johnson) Bunche was an amateur pianist who accompanied the Johnson Quartet, a musical group that comprised Ralph’s aunts and uncles. His maternal grandmother was Lucy Taylor Johnson, who was affectionately called Nana. She lived with the family, and though she could pass for white—given her partial Irish heritage—she had been born into slavery.

In 1915, Bunche and his family moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, with the hope that the state’s dry heat would improve the health of his mother and favorite uncle, Charlie, who both came down with tuberculosis. His mother died two years after the move and his uncle committed suicide three months later when he considered his poor health, his sister’s untimely death, and his inability to support the family financially. Bunche’s father, Fred, who was somewhat an outsider to the Johnson family, settled in Albuquerque for a short time. When he was unable to find work as a barber, he left the family in October 1916 and never saw his son again.

Nana, intending a fresh start in 1918, moved her two grandchildren—Bunche and his younger sister, Grace—to Los Angeles, California after hearing W.E.B. Du Bois gush about the possibilities available to blacks there. They lived in the South Central neighborhood, which was mostly white at the time. To aid his struggling family, Bunche resorted to laying carpet for a company named City Dye Works and selling newspapers. Bunche recalled this period by saying:

“I was a newsboy, had a paper route in the morning. The paper took us all on an outing down to the beach. Went on all of the rides, had quite a good time. And then in the middle of the afternoon they took us to the bath house and there the good time of myself and the other Negro newsboy ended, because we were not admitted to the bath house and I remember very vividly having to sit out and wait for a couple of hours until the other boys had done their swimming and had come out. We had to wait because we had no other means of transportation home. The humiliation of it, the resentment at the injustice of it.”

—Ralph Bunche: Model Negro Or American Other? By Charles P. Henry

While Bunche later expressed that he did not encounter any overt discrimination during his years at Jefferson High School, his grandmother discovered that black students were being placed in vocational classes on the racist assumption that none of them would attend college. Nana, a tiny, proud light-skinned Negro who emanated power, confronted the school principal and demanded that her grandson be placed in classes that would prepare him for higher education. At Jefferson High, Bunche competed in football, baseball, and track, and was a star on the basketball team. He also wrote for the campus newspaper and presided as president of the debating team.

“Nana, a tiny, proud light-skinned Negro who emanated power, confronted the school principal and demanded that her grandson be placed in classes that would prepare him for higher education.”

Under the watchful eye of Nana, Bunche graduated as valedictorian of his class and attended the University of California, Los Angeles on an athletic scholarship. A janitorial job supplied his personal needs, and his prowess in sports secured him a place on three varsity championship basketball teams. As with high school, he was also an active debater at UCLA and wrote for the campus newspaper. Having majored in international relations, Bunche graduated UCLA summa cum laude in 1927 and was again valedictorian of his class.

Bunche intended to pursue his graduate studies in political science after being offered two fellowships: one from Stanford University and another from Harvard University. He accepted the latter. One thousand dollars raised by the black community of Los Angeles also went toward this effort. A master’s degree in political science (called “government” at Harvard) came in 1928. Bunche later expressed that while he pursued his studies, he had no idea where he would go from there. On a WNBC program in cooperation with the UN called People at the United Nations, Bunche stated:

“Quite by accident I landed in teaching. There was a young professor from Howard University, who was a chemist as a matter of fact—not in the social sciences at all—doing some graduate work at Harvard. He wrote to the dean at Howard University about me as a young fellow up there in government who might have some promise and I was offered a job and that really determined the direction of my career.”

Bunche also expressed that he enjoyed teaching more than anything he had ever done. To that end, he declined to pursue a doctorate via a second fellowship from Harvard in 1928 so that he could teach at Howard. After spending part of that summer in California, he moved to Washington and was ready for the fall semester. That October, Bunche was invited by a colleague to the home of Ruth Ethel Harris, who was entertaining a group of friends who were all schoolteachers.

Talk of an upcoming dance started up and it was suggested to Bunche that he escort one of the guests named Thelma to the event. In 1973, Howard University launched an Oral Documentation Project centered on Ralph Bunche. In an interview for that project, conducted by Vincent Browne, Ruth Bunche said that rather than agreeing to take Thelma to the dance, Bunche stated that he was going to take “that quiet little girl sitting back there on the piano bench”—which was Ruth. The two remained partners for the rest of their lives and had three children together.

In the fall of 1929, Bunche returned to Harvard to complete the preliminary coursework necessary for his doctorate in government (i.e., political science). He continued in a grueling multi-year academic spree divided between teaching at Howard University and pursuing his doctorate at Harvard. He was awarded another fellowship that called for him to conduct a full year of research for a dissertation. The fieldwork was to be conducted in Europe and Africa from 1932 to 1933. The 400-plus-page-paper was completed in 1934 and accepted by the committee. The writing was of such distinction that Bunche was awarded the Robert Noxon Toppan prize for best dissertation in social sciences.

Academia held great importance for Bunche over the years, and his career is a testament to that fact. Until 1950, he was chair of the Political Science department at Howard University, which was created specifically with him in mind. He also taught at Harvard for two years, from 1950 to 1952. He served on New York City’s Board of Education for about six years and was a board member and trustee of various other prestigious institutions.

But Bunche is not cherished mainly for his academic career, nor for his civil rights efforts. He is remembered for his service to the U.S. government and the United Nations. It was his time at the UN that brought him perhaps the greatest acclaim. Between 1947 and 1949, Bunche was thrust into the midst of the Arab-Israeli conflict, as either an assistant of or secretary to a UN Committee or Commission devoted to Palestine. Things worsened in the region in early 1948 and fighting intensified, thus the UN assigned Ralph Bunche as chief aide to a Swedish nobleman and diplomat named Count Folke Bernadotte, who they appointed as mediator. The Count was assassinated four months later, however, and Bunche became acting UN mediator in the Middle East conflict.

Eleven months of intense negotiating followed, but at the end of it, Bunche secured signatures on armistice agreements from Israel and neighboring Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. This formally ended hostilities in the Arab-Israeli War. On his return home, Bunche received a hero’s welcome, complete with a ticker tape parade that wound its way up Broadway in New York City. Lecture requests poured in and he received more than thirty honorary degrees over the next three years. The NAACP also awarded him with the Spingarn Medal—their highest honor—in 1949. And Bunche was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950 for his success in the UN peace negotiation.

During his many years of faithful service, Bunche experienced discrimination in restaurants, hotels, and the government buildings he entered as an employee. This was pronounced in Washington, D.C., which was segregated, but a move to New York only proved a marginal improvement. Despite the lifelong discrimination he faced, and often downplayed, his struggle for justice and equality infused all aspects of his career. Bunche retired in 1971 due to health reasons and he died toward the end of the year on December 9, 1971. He was 68 years old. He is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

As the 28th Secretary of Defense, retired four-star general Lloyd J. Austin III made history by becoming the first black American appointed to that office.