Mary Church Terrell

A Trailblazing Advocate for Civil Rights

While Mary Church Terrell was born to two former slaves, the fortunes of her parents turned and they rose to prominence, allowing her to navigate the exclusive social circles of the middle and upper classes from her youth. She was among the few who used her wealth and social status to stem the tide of racial discrimination. While we’ve heard of the more widely publicized suffragists of the early twentieth century, Mary Church Terrell was also instrumental in advocating for women to be given the right to vote. In addition to this, Terrell served as both a professor and principal at Wilberforce University and she made history as the first black woman to be appointed to the Board of Education in the District of Columbia in 1895. She was also a founding member—as well as the first president—of the National Association of Colored Women, and she was a charter member of the NAACP.

Mary Eliza Church was born in Memphis, Tennessee on September 23, 1863, to Robert Reed Church—a businessman who became one of the first black millionaires in the South—and Louisa Ayres Church, one of the first black women to own a hair salon. While her parents had made good on their freedom by becoming successful business owners, both catering to well-to-do blacks in Memphis, they divorced during her childhood. Mary later described the relationship between her parents as cordial, and both were still highly supportive after her father remarried. She had a brother named Thomas, who, along with Mary, was taught the value of education. The affluence and influence of her parents—along with their encouragement—enabled Mary to attend Antioch College’s Model School for children located in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Since her mother considered the segregated schools in Memphis inferior, Mary received elementary and secondary education at the Ohio school, starting around age seven.

A hardworking and ambitious student, Mary—with her father’s blessing—later attended Oberlin College to receive higher education. Oberlin, which was the first white college in the U.S. to accept black students via official policy, was in the same geographical area where she received her primary education. In her autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World, Mary said of her experience at Oberlin College:

“I feel I have little reason to complain about discrimination on account of race while I was a student in Oberlin College. It would be difficult for a colored girl to go through a white school with fewer unpleasant experiences occasioned by race prejudice than I had.”

Mary was unanimously elected class poet her freshman year. And while in her senior preparatory class, a young woman who was already in a senior college class invited her to join Aelioian, the literary society of which she was a member. Mary was called to preside over meetings and represent the society in public debate. Mary also became one of the editors of the school paper, the Oberlin Review. Mary was careful to seize every opportunity available to her, and her command of the English language presented one such opportunity.

While in the Ladies Hall at noon one day, Mary received a letter from Washington, D.C. sent by a stranger who happened to be the wife of a U.S. Senator. The woman—Mrs. B. K. Bruce—was in search of a “word artist” to perform during the upcoming Inauguration. The trip to Washington yielded something far greater for Mary, however. In her autobiography, Mary wrote:

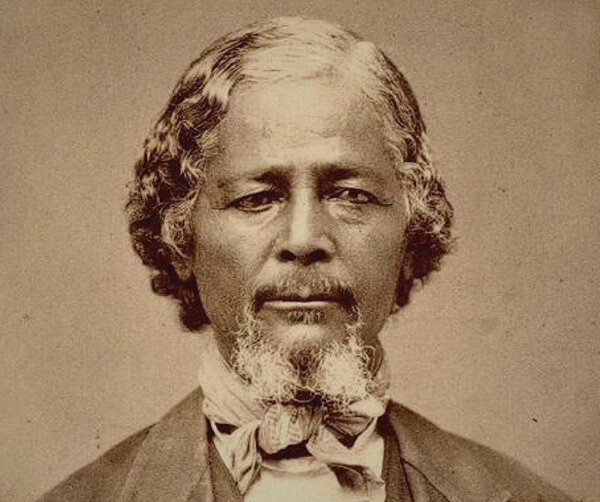

“As I was walking down the street with a friend one day, a short distance ahead of us I saw two men talking to each other. Instantly and instinctively I knew that one of the men, who had magnificent, majestic proportions and a distinguished bearing, could be none other than the great Frederick Douglass. Fortunately, my friend was well acquainted with him and introduced me to him then and there.”

With that, a lifelong friendship was established between the two, which Mary cherished beyond description. In 1884, Mary was among the first black women to graduate from Oberlin College. She earned a bachelor’s degree in Classics, namely ancient Greek, and in another four years, she earned her master’s in Education from Oberlin as well. In the interim, she taught modern languages at Wilberforce University—the historically black college in Ohio—for two years (1885–1887) and was invited to teach Latin at M Street Colored High School in Washington, D.C. in 1886.

She moved to D.C. the next year and joined M Street’s Latin Department, where she met its chair, Robert Heberton Terrell, who also taught foreign languages. After earning her master’s, Mary toured Europe for two years, traveling and studying in England, France, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy. She married Robert Heberton Terrel on October 28, 1891, in an elaborate ceremony that received glowing media coverage in both black-owned and white-owned newspapers. In addition to being an accomplished teacher and lawyer, Robert Terrell also had the distinction of becoming the first black municipal court judge in Washington, D.C. Black College-educated people looking to pursue professional careers in those days only found work opportunities at segregated schools and businesses. Mary experienced this as well, but after getting married, her working days ended. By law, married women were barred from teaching, so Mary resorted to managing her household.

“Robert Terrell also had the distinction of becoming the first black municipal court judge in Washington, D.C.”

Early in her marriage, she suffered three miscarriages due to the substandard condition of segregated medical facilities available to blacks. But the couple eventually had a healthy daughter who survived. They named her Phyllis, after the eighteenth-century poetess Phillis Wheatley. They also adopted her brother’s daughter, Mary Louisa, in 1905. The event that roused Mary from the settled married life she was living in D.C. was the lynching of her lifelong friend, Thomas Moss. Whites in Memphis who considered Moss a rival killed him and two co-owners simply because the black-owned grocery competed with their white-owned store.

The blatant injustice of the racial violence struck Mary deeply, and it compelled her to accompany Frederick Douglass to the White House to urge the President of the United States, Benjamin Harrison, to boldly denounce the lynching in his annual address to the public. President Harrison refused their request.

A popular newspaper columnist and editor at the time, Ida B. Wells often used the platform to criticize racial injustice and inequality. Mary joined her friend Ida in organizing anti-lynching campaigns that drew advocates to the cause and created awareness of racial cruelty. Mary and Ida joined forces again and, together with Harriet Tubman and other black women leaders, formed the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896. The NACW was the largest and most prominent federation of black women’s clubs during the black suffrage movement, of which Mary was elected its first president. She presided from 1896 to 1901, and she also created the association’s motto, “Lifting as we climb,” which encompassed the goals of the association: desegregation, securing the right for women to vote, and equal rights for blacks.

Mary used her position as NACW president to advance various social and educational reforms by writing and speaking extensively. She advocated strongly for the rights of black women because, being one herself, she knew firsthand the twin obstacles every black woman faced:

“... both sex and race,” Mary wrote in her autobiography. “I belong to the only group in this country which has two such huge obstacles to surmount.”

Mary’s gift for language allowed her to effectively convey the struggle of black women in America in a way those residing outside of that struggle could understand. Her ability to articulate the black struggle also took her to Europe, and she addressed an audience at the International Congress of Women in Berlin on June 13, 1904, speaking both German and French. Prominent black leaders W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington also invited Mary to their respective schools to give commencement speeches. And at the urging of Du Bois, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) made Mary a founding member. She signed the charter in 1909.

The collective efforts of suffragists paid off in 1920, with the passage of the 19th Amendment, allowing women the right to vote. Mary was therefore free to focus on other areas of activism, chiefly civil rights. But even though she dedicated herself to these causes, Mary still managed to raise two daughters and successfully run her household. After her husband Robert died from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1925, Mary traveled outside of Washington, D.C. less often for the remainder of her life.

Up into her later years, Mary remained committed to abolishing Jim Crow laws. In 1949, she won an anti-discrimination lawsuit that allowed her to become the first black member of the American Association of University Women. Mary was also instrumental in ending segregation in restaurants in Washington, D.C. On February 28, 1950, when Mary was 86 years old, she purposefully invited a few friends to lunch at a segregated downtown cafeteria named Thompson’s. Only one of her friends was white. The manager refused to serve the group based on anti-black policies. The group left without eating, but Mary and other activists sued Thompson’s shortly after, based on a “lost law” dating back to 1872 (the Equal Services Act) that made it illegal for D.C. restaurants to refuse service to patrons because of their race.

The case wound its way through the courts and eventually made its way to the Supreme Court. Mary focused on other restaurants in the meantime, by organizing activists to boycott, picket, and hold sit-ins against these segregated establishments. In the end—that being 1953— segregated restaurants in Washington, D.C. were declared unconstitutional. Mary Church Terrell died on July 24, 1954, at Anne Arundel General Hospital (now known as Anne Arundel Medical Center) in Annapolis, Maryland. She was 90 years old. Just two months before her death, Mary witnessed the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling, which put an end to segregated schools.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Ida B. Wells was an unsung early civil rights leader, suffragist, researcher, and journalist who used her pen in ways that are yet to be rivaled.