Isaac Burns Murphy

Arguably the Greatest American Jockey

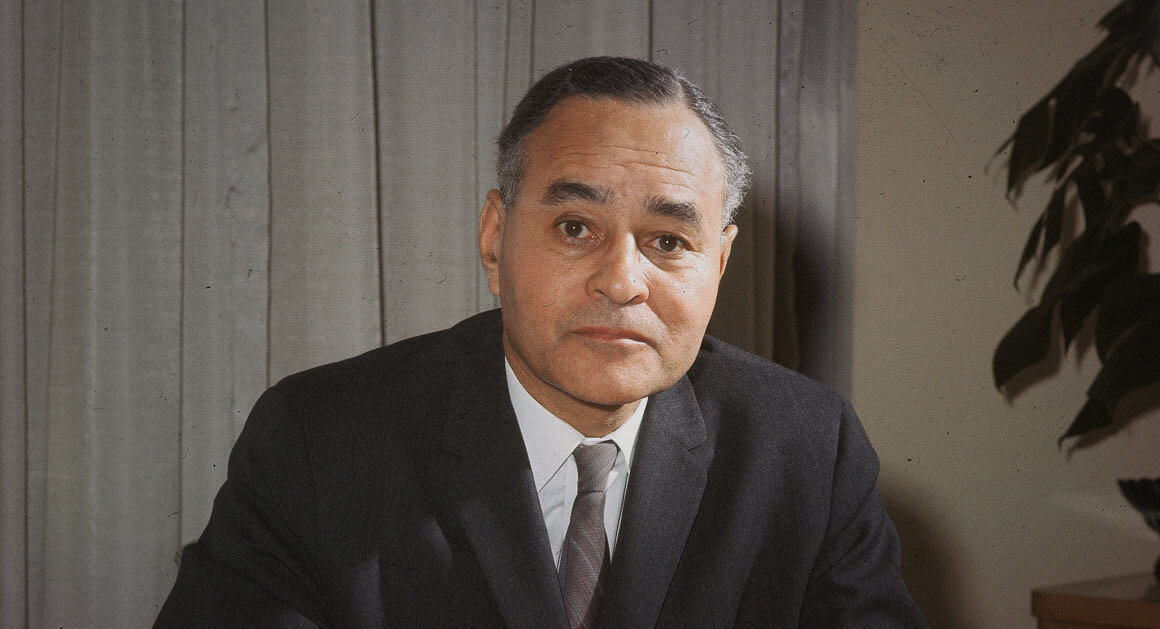

Portrait of Isaac Burns Murphy. Photo courtesy of the Kentucky Horse Park.

Isaac Burns Murphy is considered by some to be the greatest rider in the history of American Thoroughbred horse racing. While Murphy was black, he was hardly the only black jockey of his era, because black Americans dominated the sport in that period. But Murphy was the preeminent rider among them. More recent jockeys have grabbed headlines and wowed audiences by winning prestigious races and earning multiple millions in prize money, but the stats should speak for themselves.

Russell Avery Baze waving to fans. Photo courtesy of Dustin Orona.

Touted as one of the greatest horse jockeys in living memory, Russell Avery Baze, who won 12,844 races, had a career average of over 24 percent in terms of wins. Put another way, that means almost one in every four horses he rode during a race was a winner. That stands as an industry-best when you remove Isaac Burns Murphy from the equation. Murphy himself admitted to winning 44 percent of the races he entered. Records from that time only show an average of 34.5 percent of wins, however. But many of his races were likely never entered into the chart books, which was not uncommon in those days. Regardless, a 34.5 percent winning average is yet to be matched by any other horse racing jockey, meaning Murphy set what is perhaps an unachievable standard in the sport. Horse racing Hall of Fame jockey Eddie Arcaro said of Murphy:

“There is no chance that his record of winning will ever be surpassed.”¹

Isaac Burns Murphy was born free in Fayette County, Kentucky on April 16, 1861, but his parents were former slaves. His father served in the Union army during the Civil War and spent his final days as a prisoner of war in the hands of the Confederate army. Following his death, Murphy’s mother moved the family to Lexington, Kentucky, where he grew up. Murphy’s racing career started in 1875, and he originated what came to be known as the grandstand finish, which was a thrilling charge to the finish line where he rode upright after pacing himself throughout the race. He was known across the nation after a major 1879 win during the Travers Stakes in Saratoga Springs, New York.

Churchill Downs Racetrack, in Louisville, Kentucky. Home of the Kentucky Derby and the Kentucky Oaks since 1875. Photo in the public domain.

Murphy was the first to win the Kentucky Derby three times, having competed in eleven, and he was also the first to win consecutive Derbies—1890 and 1891. He made history by winning the Kentucky Derby, the Kentucky Oaks, and the Clark Handicap in the same year—1884, and he was the first person of any ethnicity elected to horse racing’s Hall of Fame. Murphy also developed a reputation as a man of integrity. When horse bettors attempted to bribe him to lose the Kenner Stakes in 1879 he refused. Murphy’s many wins positioned him as one of the highest-paid athletes of any sport played in the U.S. at the time. His earnings allowed him to both own and train horses, which required considerable sums of money.

But sadly, Murphy’s career started on a steady decline in the mid-1890s mainly due to objectionable habits he adopted that not only affected his health but also his weight. The timing of his downfall coincided with the period of increased racism experienced by blacks in horse racing. Their involvement with the sport decreased considerably as a result. In the years following World War I, black jockeys were largely forgotten. In a 2009 Smithsonian Magazine article titled, “The Kentucky Derby’s Forgotten Jockeys,” Lisa K. Winkler wrote:

“In the first Kentucky Derby in 1875, 13 out of 15 jockeys were black. Among the first 28 derby winners, 15 were black.”

Winkler also pointed out in 2009 that when considering modern Kentucky Derby races, where thousands of fans line up to watch the celebrated event, an unusual phenomenon was witnessed in an American sport that year:

“Of some 20 riders, none are African-American.”

That changed in 2013 when black jockey Kevin Krigger competed in the Kentucky Derby. In 2021, another black jockey named Kendrick Carmouche rode in the prestigious event, of which the Associated Press reported:

“Carmouche is now one of the few remaining Black jockeys in the U.S. Much like Marlon St. Julien in 2000, Patrick Husbands in 2006, and Kevin Krigger in 2013, his presence in horse racing’s biggest event is a reminder of how the industry marginalized black jockeys to the point they all but disappeared from the sport.”

When Isaac Murphy died of pneumonia on February 12, 1896, he was thereafter buried in an unmarked grave, despite his past fame and many hard-won successes. It was not until the late 1960s that his burial site was located by a Kentucky researcher. Murphy’s body was then exhumed and reburied in a fitting burial site in the Kentucky Horse Park. Isaac Murphy’s great legacy is now starting to be remembered.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Simone Biles is the most decorated gymnast in U.S. history, having won more than two dozen Olympic and World Championship medals thus far.