Lucy Terry

Composer of the Oldest Existing Poem by a Black American

Painted rendering of Lucy Terry, courtesy of artist Louise Minks and the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA.

While Jupiter Hammon and Phillis Wheatley are credited as pioneering black poets, another black poet preceded them both in the annals of history with a piece that remained unpublished until 1855. Her name was Lucy Terry. Lucy’s gift for storytelling was unparalleled. The one work that survives from her collective output is “Bars Fight,” a 28-line narrative poem that recounts an attack on a colonial village by Abenaki natives. “Bars Fight” was composed in 1746, and the “Bars” referred to in the title is colonial-speak for a meadow, which was the setting for the attack in the Franklin County, Massachusetts village known as Deerfield.

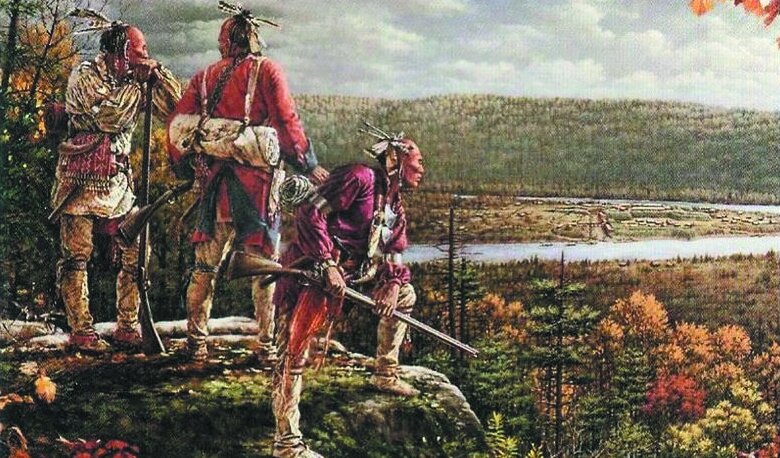

Painting of Abenaki natives, by Robert Griffing.

Lucy was present during the raid on the village that took place on August 25, 1746, and she witnessed firsthand the atrocities mentioned in her poem. Five white settlers were killed, one suffered mortal injuries, one escaped across a river, and another was taken captive to Canada. For over a century, Lucy’s poem only enjoyed oral preservation, until it was published in a collection titled, History of Western Massachusetts by American poet and novelist Josiah Gilbert Holland. After its publication, however, “Bars Fight” fell into obscurity and was not rediscovered until 1942. That is the year the poem found its way into print a second time after almost another century. Lorenzo Greene, a history professor and author, published it in his book, The Negro in Colonial New England 1620–1776.

Bars Fight

By Lucy Terry

August ’twas the twenty-fifth,

Seventeen hundred forty-six;

The Indians did in ambush lay,

Some very valient men to slay,

The names of whom I’ll not leave out.

Samuel Allen like a hero fout,

And though he was so brave and bold,

His face no more shall we behold.

Eleazer Hawks was killed outright,

Before he had time to fight—

Before he did the Indians see,

Was shot and killed immediately.

Oliver Amsden he was slain,

Which caused his friends much grief and pain.

Simeon Amsden they found dead,

Not many rods distant from his head.

Adonijah Gillett we do hear

Did lose his life which was so dear.

John Sadler fled across the water,

And thus escaped the dreadful slaughter.

Eunice Allen see the Indians coming,

And hopes to save herself by running,

And had not her petticoats stopped her,

The awful creatures had not catched her,

Nor tommy hawked her on her head,

And left her on the ground for dead.

Young Samuel Allen, Oh lack-a-day! Was taken and carried to Canada.

For many years, it was thought that Lucy put pen to paper when composing her poem, but recent scholarship suggests that, though she was literate, she may have relied on African oral tradition and merely recited what she had composed in her mind. Others in Deerfield Village later memorized and retold the epic poem and thereby kept both it and her name in remembrance. Support for this theory comes from the earliest known record of the poem in written form, which is traced to an 1819 lecture. This was followed by its first official printing in 1855.

Lucy Terry was born in Africa in 1724. She was kidnapped in childhood and shipped to Bristol, Rhode Island. At only four years of age, Lucy was sold to Ebenezer Wells, a Deerfield, Massachusetts resident who owned a tavern in the village. Lucy was brought to live with Wells and his wife, who were childless. In 1735, during the Great Awakening, Lucy was baptized with the approval of Wells and she became a full church member in 1744, at the age of twenty. She remained a slave of the Wellses for another twelve years.

Her freedom came as a result of her marriage to a free black man named Abijah Prince, whom she wed in 1756. She was thereafter known as Lucy Prince. It is uncertain whether Wells released her from bondage or Abijah Prince purchased her freedom. In either case, Lucy was no longer a slave. The couple’s first child was born in 1757, and they had five other children by 1769. They also moved to Guilford, Vermont in 1764. Two of their sons later served in the Revolutionary War.

Terry, who was known for her storytelling abilities since her youth, was also a seasoned orator. A white colonel named Eli Bronson once attempted to steal land from the Prince family by making false claims, and the case went before the Vermont Supreme Court. Despite hiring an attorney, Lucy, in a rare show of eloquence, successfully argued her case. She was opposed by two experienced litigators, one of whom was later elected chief justice. Lucy, who was the first woman to argue a case before Vermont’s high court, was awarded $200.

Lucy Terry Prince passed away on July 11, 1821. She was a remarkable woman, and the respect paid to her in death is a testament to that fact. In Lucy’s day, obituaries written for deceased females were notorious for their brevity and inaccuracy. When Lucy’s obituary was read on Tuesday, August 21, 1821, it was unusually long and full of praise, as well as accurate details of her life. It was also printed in two papers, first in the Vermont Gazette, headquartered in Bennington, Vermont, and then in the Franklin Herald of Greenfield, Massachusetts. This highlights the level of importance Lucy commanded during her lifetime. A few lines from her obituary paint a clear picture of how she was regarded by those who came to know her:

“In this remarkable woman there was an assemblage of qualities rarely to be found among her sex. Her volubility was exceeded by none, and in general the fluency of her speech was not destitute of instruction and education. She was much respected among her acquaintances, who treated her with a degree of deference.”

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in 45 People, Places, and Events in Black History You Should Know.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Ida B. Wells was an unsung early civil rights leader, suffragist, researcher, and journalist who used her pen in ways that are yet to be rivaled.