Paul Cuffee

The Wealthy Shipping Magnate and Black Nationalist

Portrait of Captain Paul Cuffee.

Paul Cuffee was a respected sea captain and entrepreneur whose maritime trading ventures amassed a tidy fortune. Cuffee is the first black American in history to spearhead a back-to-Africa movement, preceding pan-Africanists Martin R. Delany, Henry Highland Garnet, Marcus Garvey, and many others. And on May 2, 1812—before the United States engaged in armed conflict with Great Britain—Cuffee made history by becoming the first free black American to meet with a sitting U.S. president.

Paul Cuffee (also spelled Cuffe) was born on January 17, 1759, on Cuttyhunk Island, part of the Elizabeth Islands in southeastern Massachusetts. Cuffee’s father was Kofi Slocum, a formerly enslaved Ashanti farmer from Ghana. “Cuffee” is the Anglicized form of “Kofi,” which Paul Cuffee adopted from his father. Cuffee’s mother was a Wampanoag woman from Harwich, Cape Cod named Ruth Moses, whom his father married in Dartmouth in 1747. The couple owned a 116-acre farm in Westport, Massachusetts. When Cuffee was around thirteen years old, his father died, leaving the farm in the hands of Ruth, who had life rights. Cuffee and his older brother John inherited the farm and lived there with Ruth and their three younger sisters.

Cuffee decided on a life of whaling in a few short months and left management of the farm to his brother John. In 1773, Cuffee became a crew member of a whaling vessel bound for the West Indies and repeated the experience by crewing two more ships in 1775 and 1776. On his final voyage, in the fateful year of the American Revolution, the British Royal Navy captured Cuffe and imprisoned him at New York harbor for three months before his parole.

Cuffee returned to Westport and partnered with his older brother David on a new venture. Cuffee used a sloop—a small one-masted sailboat—to slip through a British blockade to deliver supplies to Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket during the war. The British banned American commerce, but Cuffee penetrated the blockade repeatedly and deepened relations with influential Quakers, including lifelong business partners William Rotch and his son of the same name. Cuffee and his brother also faced pirates during this period and lost supplies and one sailboat to them on a night voyage. While David decided to leave the partnership, Cuffee built his mercantile empire on this blockade-running foundation and later became a Quaker by joining the Society of Friends in 1808. In a few decades, Cuffee was regarded along the east coast as a successful entrepreneur and sea captain and among the wealthiest free blacks in the U.S.

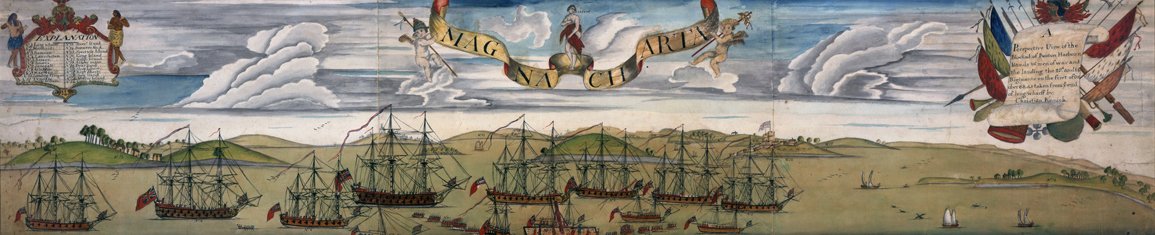

British warships form a blockade in Boston harbor.

As a prominent black landowner and respected businessman, Cuffee saw the glaring inequality between blacks and whites. In 1780, at age 21, he protested taxes and advocated for voting rights along with his brother John and five other free black Americans. Together they petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for voting rights equal to their white landowning neighbors. The House of Representatives denied their petition, and authorities imprisoned the Cuffee brothers for a few days for refusing to pay poll taxes the previous two years. A lawyer named Walter Spooner defended the Cuffee brothers. He negotiated a fair settlement that reduced their taxes and led to their freedom. And a 1783 judicial act granted taxpaying black males in Massachusetts the right to vote.

Like his father, Cuffee married a prominent Wampanoag descendant, Alice Abel Pequit, in 1783, and they settled down to a quiet life. As Cuffee expanded his maritime ventures, he fathered seven children in between—two sons and five daughters. The year he married, Cuffee partnered with his brother-in-law, Michael Wainer, a Wampanoag man. Wainer married Cuffee’s older sister, Mary, in 1772. Cuffee and Wainer’s shipping enterprise eventually spread from the South Coast of Massachusetts to Connecticut and then further along the East Coast, up to Canada. They held waterfront properties and built massive sailing ships to carry trade goods. Cuffee’s nephews crewed those ships when they matured.

View of Cuffee Wharf at 1430-1436 Drift Road, Westport, Massachusetts. The property sat at the end of a private drive, with the wharf on the West Bank of the East Branch of the Acoaxet River (now Westport River).

Both Cuffee and Wainer acquired additional properties as their trading business grew. Cuffee built his house next to his Westport shipyard, which served a small fleet. He also used his wealth to support various local causes, including a smallpox hospital and an integrated school built on his property—arguably the first of its kind in the U.S. In addition to establishing business relations with influential Quakers, Cuffee’s maritime ventures also allowed him to engage with prominent abolitionists in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and London. The British saw promise in Cuffee and looked to him to aid their efforts to create a new African colony for formerly enslaved blacks from America and England. Sierra Leone, which began to be colonized by blacks from England in 1787, became the focus of the first back-to-Africa movement.

Sierra Leone held great promise as a picture of freedom and an end to racial oppression and injustice. Cuffee also endeavored to position the colony as the center of a new black economy. In his view, the production and trade of West African goods could be expanded internationally and diminish the slave trade. With these goals in mind, he set sail for Sierra Leone in 1810 aboard the Traveller, the first of several voyages. On April 19, 1812, as the Traveller returned from Sierra Leone, the ship’s African and British goods were seized by customs officers on Rhode Island. President James Madison had signed the Nonintercourse Act of 1811, which barred the trade of British goods. Cuffee moved quickly and secured letters of support and introduction from various Federalists. He carried those letters on a trip to the capital the following month, where he met with President James Madison at the White House.

In the wake of their discussion, Cuffee recovered his ship and cargo. On December 10, 1815, Cuffee made another voyage to Sierra Leone, now carrying thirty-eight passengers, all black Americans intent on starting a new life in West Africa. But despite those seeds of promise, Cuffee’s dream never came to fruition.

Benjamin “Pap” Singleton was a land promoter and black nationalist who led thousands of blacks west during the post-Reconstruction era in what was called the Great Migration.